From June 25-29, 2021, the Pacific Northwest and Southwest Canada experienced a multi-day heatwave resulting in record-breaking temperatures that affected even the coastal communities in Grays Harbor County.

Hoquiam recorded a temperature of 103 degrees, and Ocean Shores, which usually has June days averaging temperatures in the 60s, posted 90 degrees.

This heatwave became known as the 2021 Heat Dome. In the subsequent days, Adam Sibley, a post-doctoral student at Oregon State University who had defended his PhD a few weeks earlier, found himself on an email chain with scientists who asked if others had seen trees scorched by the heat wave.

“And that very quickly grew into a much bigger e-mail with more and more people added on to it,” Sibley said. “People from all over Oregon, Washington, British Columbia saying, ‘Yeah, I see that over here too.’ We knew pretty immediately how big the phenomenon was.”

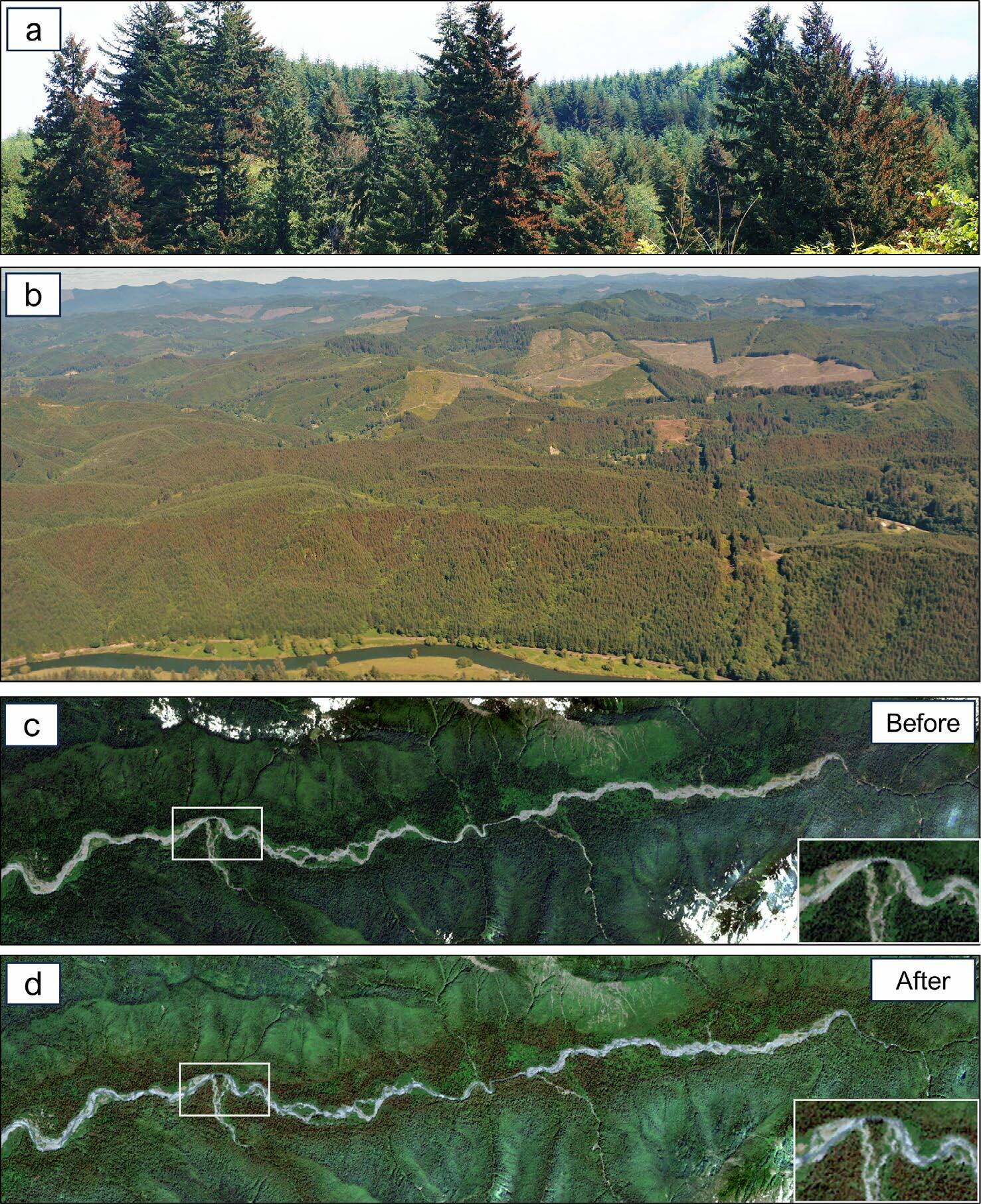

Trees with foliar scorch have leaves that are red, brown, or orange instead of green; this indicates that the leaves are dying or have died. Foliar scorch can happen when a tree is too close to flames or if the tree is in a particularly hot microsite. Scorch also typically is at the individual tree level, not region wide.

“The thing that was unique about this is that it was a very quick, short-term response to really hot weather,” said Sibley.

Oregon State University convened a mini-symposium on the 2021 Heat Dome, from which researchers generated hypotheses to research. Sibley undertook a study analyzing the extent of the foliar scorch and why some trees were affected than others. A significant finding was an estimated 725,368 acres of forest were scorched across the Pacific Northwest.

To learn more about findings, specifically as they pertain to the Olympic Peninsula, The Daily World spoke with Sibley, who is now a remote sensing scientist with Chloris Geospatial based in Massachusetts.

What follows is our conversation edited for length and clarity.

The Daily World: What were the physiological processes that caused the scorch people observed following the heat dome?

Sibley: In this particular case, it seems that the combination of high air temperatures and needles that were exposed to full sunlight had their temperatures raised beyond critical thresholds where cell membranes start to leak. The cell wall contains the vital materials of the cell, and if it gets too hot, those cell walls can become overly leaky and the cell dies. And when photosystems that are meant to be observing sunlight to do photosynthesis get to these critical temperatures, they’re unable to do that.

TDW: How did you determine to study the extent of the scorch?

Sibley: Dave Bell [a research forester with the US Forest Service] and Matt Gregory [a faculty research assistant in Oregon State University Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society] did a pilot to see if the scorch could be mapped, and their pilot showed that that could be done.

In terms of figuring out what the study area should be, it was based around the reports that we had gotten of on-the-ground observations of the scorch and then we knew the area to expand to.

Chris Still, a professor with Oregon State University College of Forestry, led the mini-symposium on the Heat Dome to bring together scientists, industry folks, and public land managers to talk about what they had seen and what their experiences were. That mini- symposium helped us generate quite a number of hypotheses. One is that it was worse on sun-exposed sides of the tree than on shaded parts of the tree. People had also observed that certain species seemed to be particularly affected so we were definitely going to see how this played out species by species.

TDW: How helpful was the availability of satellite imagery to determine the extent of the scorch?

Sibley: It was incredibly useful, and we also had good fortune there was basically wall-to-wall clean observations, meaning without much cloud contamination just before the heat wave and just after the heat wave. That’s so important because you could imagine that there’s other reasons that trees would have their needles killed, so we can’t be sure if this came from the heat wave or if this came from something else.

But being able to look right before the heat wave and establish which trees were healthy and green and then looking immediately after the heat wave and seeing those green, healthy trees are now orange or red really enabled us to attribute those dead needles to the heat dome.

TDW: Were the spatial hotspots that you described in the paper visually obvious in the satellite imagery?

Sibley: It was definitely encouraging to see that just with the naked eye; it didn’t require looking at different combinations of wavelengths or sophisticated techniques for seeing it. We started by focusing on the Oregon coast because that’s where we had all seen it ourselves, and then we were able to see those patterns manifest on which hill slopes had more damage and which had less.

TDW: And one of those hot spots was on the Olympic Peninsula, right?

Sibley: Yes. When I first made the wall-to-wall map classified by scorch or non-scorch, I saw a big blob of scorch up there that we had not known was as intense as it was. And my first reaction was, ‘This must be some mistake that I made.’ But then I went to the imagery and looked at the before and after and I was like, ‘Holy cow. These forests were definitely significantly affected.’

TDW: Western hemlock, western redcedar, and Sitka spruce were called out as being more affected by the excessive heat than the Douglas-fir and red alder. Why was this?

Sibley: We’ve hypothesized that it might have something to do with the life history of these different trees, specifically that red cedar and western hemlock start their lives as shade-tolerant trees and tend to be growing in the understory of the taller Douglas fir. Douglas fir, on the other hand, from the time that it’s a seedling all the way up [to maturity], is often tolerating full sunlight and the hottest conditions that are experienced by the forest. So for western hemlock and western redcedar, they don’t appear to be as well-equipped at handling high temperatures as Douglas-fir is.

TDW: I also thought it interesting that in the journal article, it’s mentioned that during the heat wave there were clear skies over the Olympic Peninsula, whereas normally it’s overcast.

Sibley: The combination [of cloud cover] seemed to be very important. On the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest in Oregon, Mark Schulze [H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest Director] observed that a stand with a mixture of Douglas-fir and western hemlock, the western hemlocks in the shade of a larger Douglas-fir did much better than those that had full sun exposure. The ones with full sun exposure were scorched.

That was very suggestive that the direct sunlight was either doing photosystem damage or adding to the thermal load of the leaves and was harder for the hemlock to tolerate than the Douglas-fir.

TDW: In the journal article, bud burst was also cited as a contributor for why some of the trees experience more scorch more than others. Can you explain what is bud burst and what prompted looking at this variable?

Sibley: When a Douglas-fir tree is going to grow new twig with new needles on it, all of those components start as a little bud. And there’s a certain time in the spring that tends to be triggered by the accumulation of temperature. When it’s been warm enough for long enough in the spring, that bud will burst open and those new needles will come out and start expanding and developing.

In that period of expansion and development, it’s a vulnerable time for those leaves. They are going to be less able to regulate water loss for one thing. Depending on when the heat dome caught trees in that developmental stage, they may have been more vulnerable.

What prompted looking at it was trying to understand why places in Southern Oregon where it was also very, very hot during the heat dome didn’t seem to have as much of this scorch as the northern half of the state. The theory was that the trees in the south were further along in their springtime development. They had needles that were more mature and more hardened to handle the high temperatures.

TDW: What are takeaways that you’ve learned about how trees respond to extreme heat?

Sibley: The biggest reaction that I had to this was the fact that this is an emerging phenomenon or a new phenomenon; we can’t find another example of it happening in the historical record.

On the one hand, the good news is that these trees that had their needles die by and large, there haven’t been reports of the whole mature tree dying. Seedlings and saplings were killed in some instances, but mature trees seem to have largely recovered from it, so that’s a positive takeaway. But what might happen if the heat dome was a couple degrees hotter than it was?

TDW: For this study, you used satellite imagery taken by Sentinel-2 [which was launched by the European Space Agency] and temperature data collected by the PRISM Climate Group [which is located at Oregon State University]. How valuable is it to have this scientific infrastructure to answer these types of research questions?

Sibley: It is hugely valuable, and I would add on top of those two data sources the Lemma maps of tree species [Landscape Ecology, Modeling, Mapping & Analysis is a team staffed by employees with the USDA Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station and Oregon State University Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society].

As a postdoc with research funding from the U.S. Geological Survey Climate Adaptation Science Center but not a big research budget to spend on equipment or data, that these data sets are freely available and that decades of hard work and focus have gone into developing them was essential for this study. There’s no other way that it could have been done without those resources already being there.

TDW: Any last thoughts to share about the value of this research?

Sibley: In terms of addressing the value, not just scientists or foresters experienced this heat dome. Everybody in the Pacific Northwest received it as kind of a shock, and there were many people who were curious, worried, and troubled about what they saw that happened to the trees.

Rather than be in the dark about the specifics of it and not knowing why it happened, the alternative is to have the tools that are required to know and to understand it. And understanding these things is the first step in planning for the resiliency of the forests.

Many people in the Pacific Northwest love these forests and doing these studies and having these resources are really in the public benefit.

“Extreme Heatwave Causes Immediate, Widespread Mortality of Forest Canopy Foliage, Highlighting Modes of Forest Sensitivity to Extreme Heat” published in Global Change Biology is available at https://www.fs.usda.gov/pnw/pubs/journals/pnw_2025_sibley001.pdf.