DEAR READER: “You don’t have to burn books to destroy a culture. Just get people to stop reading them,” Ray Bradbury once observed. His incendiary 1953 novel, “Fahrenheit 451,” is a cautionary tale about a future authoritarian America where books have been outlawed and the regime’s stormtrooper “firemen” burn any they uncover. Science fiction doesn’t get much scarier.

When Bradbury was a teenager, Germany’s young Nazis, eyes glistening with inculcated hatred, were busy consigning “subversive” books to campus bonfires, especially any by Jews. “It terrified me,” Bradbury recalled, adding that “Fahrenheit 451” was also influenced by Stalin’s repression of his political enemies, including writers and poets. The Soviet dictator executed at least 750,000 erstwhile comrades during the 1930s after show trials. “They burned the authors instead of the books,” Bradbury said.

But chiefly on his mind while writing “Fahrenheit 451,” Bradbury said, was Joseph McCarthy’s reckless Red-baiting. There were commies and “fellow travelers” everywhere, the Wisconsin senator charged, from the halls of the State Department to Hollywood sound stages and university classrooms. Even President Eisenhower was “soft” on communism, McCarthy warned. With that, the senator had finally gone too far.

Here in Washington, we had our own ambitious McCarthy copycat in State Rep. Albert Canwell, a right-wing Republican from Spokane. Proud of his irrational bigotry, Canwell declared, “If someone insists that there is discrimination against Negroes in this country, or that there is inequality of wealth, there is every reason to believe that person is a Communist.” (In an interview years later, Canwell informed me that Gov. Dan Evans was a socialist and Attorney General Slade Gorton a pretend Republican with “pinko” pals.)

It’s worth remembering, too, that in a 1994 interview, Ray Bradbury denounced political correctness — right and left — as “the real enemy these days,” labeling it as “thought control and freedom-of-speech control.”

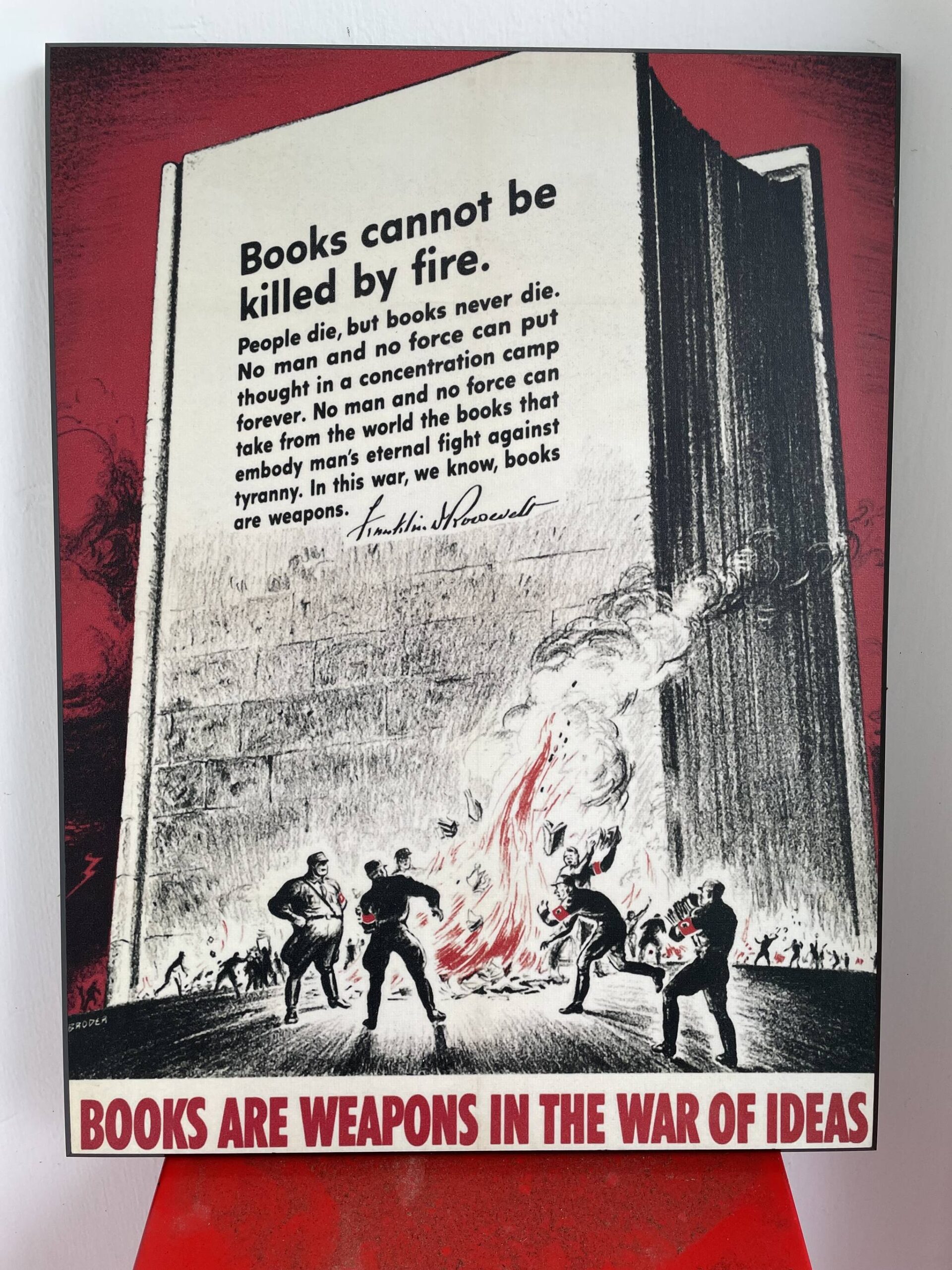

The World War II poster illustrating this column is one I treasure. It quotes Franklin D. Roosevelt’s stirring proclamation:

Books cannot be killed by fire. People die, but books never die. No man and no force can put thought in a concentration camp forever. No man and no force can take from the world the books that embody man’s eternal fight against tyranny. In this war, we know, books are weapons.

IN THIS COLUMN, and the next, I’ll share my list of the 10 best new books I’ve read this year. The first, with America set to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence next year, is the perfect holiday gift for serious readers.

#1: “We the People, A History of the U.S. Constitution,” by Jill Lepore.

Lepore is a professor of history and law at Harvard University and a staff writer at The New Yorker magazine. In other words, a shoo-in for President Trump’s ever-expanding enemies list. The president could edify himself and do we the people a great service by reading Lepore’s masterful analysis of the Founding Fathers’ complicated intentions. “Parchment decays and ink fades, but ideas endure; they also change,” Lepore writes, noting that one of their goals in 1787 was “to allow for change without violence,” or to put it another way, “endurance through adaptation.” They deliberately made change difficult, requiring House and Senate supermajorities for proposed constitutional amendments, with veto power to the states through their legislatures. Gaining the consent of three-fourths of the states is a high bar. The Equal Rights Amendment, introduced in 1923, finally cleared Congress in 1972. Ten years later — after two deadlines were extended — it was still three states short of ratification. Today, the seemingly self-evident truth that “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex” remains in limbo.

Exploring all this and much more, Lepore is not just a meticulous historian; she is a brilliant writer. “The U.S. Constitution, made from the hides of fleeced sheep, the feathers of molting geese, and sunbeams and shafts of light, is not perfect and never was perfect and never will be perfect,” Lepore writes. Then she reminds us that an older, wiser Thomas Jefferson observed this in 1816: “Some men look at constitutions with sanctimonious reverence, and deem them like the arc of the covenant, too sacred to be touched. … They ascribe to the men of the preceding age a wisdom more than human, and suppose what they did to be beyond amendment.”

#2. “The Prosecutor, One Man’s Battle to Bring Nazis to Justice,” by Jack Fairweather.

This is the true story of Fritz Bauer, a gay, Jewish lawyer who was the youngest district judge in Germany before the Nazis came to power. Having survived Hitler’s concentration camps, Bauer “made it his postwar mission to force his countrymen to confront their complicity in the genocide.” That he succeeded, thwarting the network of former Nazis who still ran the country, is one of the last century’s most persistent profiles in courage.

#3: “The Trees are Speaking, Dispatches from the Salmon Forests,” by Lynda V. Mapes.

The finest reporter I’ve ever known, Mapes spent nearly three decades covering the environment and Northwest tribal nations for The Seattle Times. We have crossed paths and compared notes many times since 1993 when we covered Clinton’s Northwest Forest Conference in Portland. What struck me immediately back then was Mapes’ empathy for my timber-town people — collateral damage to this day in the war to protect old-growth ecosystems and their surrogate, the now even more hapless northern spotted owl. “The Trees are Speaking” is the work of an extraordinary journalist with a poet’s soul. Mapes takes us on a bicoastal forestland journey, from the western slope of the Cascades to downeast Maine.

#4: “Red Harbor, Radical Workers and Community Struggle in the Pacific Northwest,” by Aaron Goings.

Previously reviewed at length in this column, “Red Harbor” is a painstakingly researched account of class warfare on Grays Harbor during the first four decades of the 20th century. Replete with revelations about the Harbor’s large Finnish population and the local strength of the Ku Klux Klan, Goings’ book is essential to an objective understanding of our polarizing local history.

#5: “Fighting for the Puyallup Tribe,” a memoir by Ramona Bennett Bill.

I first met Ramona in the 1970s while covering the “fish-ins” staged by Northwest tribes to protect their treaty rights. As brave and resourceful as any male warrior in the annals of indigenous American history, Ramona — unsurprisingly — is also a gifted writer, with a wry sense of humor. “The original people belonging on this continent are called Indians because Columbus was looking for India,” she writes. “We’re glad he wasn’t looking for Turkey, or we’d be called Turkeys.”

Next week: Five more.

John C. Hughes was chief historian for the Office of the Secretary of State for 17 years after retiring as editor and publisher of The Daily World in 2008.