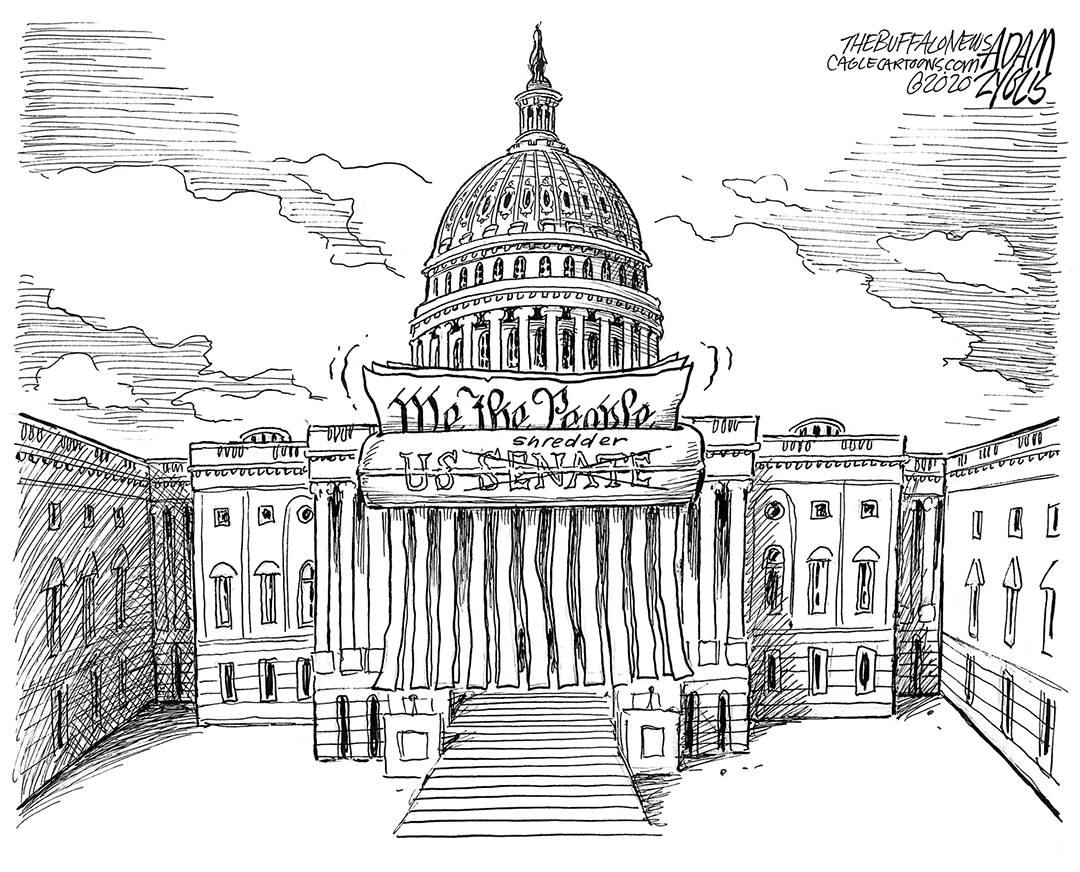

Let’s take a deep breath as we consider the remarkable event that occurred in the U.S. Senate on Jan. 31, when 51 senators voted to conduct a constitutionally obligatory trial of an impeached president without looking at readily available, relevant evidence.

How bad was it, really? Was it the day the sky began to fall? Will we someday associate Jan. 31, 2020 with dates like Dec. 7, 1941 or Sept. 11, 2001?

On the evening of the vote, comedian Bill Maher was already talking about Jan. 31 as the day the rule of law died in our country. Accurately anticipating the vote the day before, Washington Post columnist Dana Milbank said that once right becomes whatever the president says it is, “We are lost.”

On the other hand, the day after the vote, former FBI director James Comey recommended a more restrained response. He described the cultural turmoil of his childhood: the assassinations of John and Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X; Vietnam; Watergate; and so on.

So relax, he says, it’s not a big deal. The “United States didn’t come apart. It won’t now.”

Of course, James Comey is not renowned for good judgment and wisdom. We underestimate the gravity of what happened on Jan. 31 in the Senate —and the acquittal that will probably occur on Feb. 5 —at our peril.

Senate Republicans did their best to minimize the seriousness of the essential charge against the president, that he withheld crucial military aid in order to coerce Ukraine into announcing an investigation that he thought would benefit him politically. But let’s not mince words: Trump used the power of his office in an attempt to cheat in an American election.

That idea ought to stun us. In fact, it’s so outrageous that Republican resistance to it had to find ways to gradually accommodate itself to the notion that any American president would do such a thing.

At first Republicans argued that it didn’t happen. In the face of a great deal of credible evidence that it did occur, they turned their attention to the “process,” making a number of false allegations about the manner in which the articles of impeachment were produced in the House.

Republicans claimed that the allegations against Trump are based in pure partisanship, because every House Republican refused to vote for them. Which reminds me of the joke about the man who murdered his parents, then threw himself upon the mercy of the court because he was an orphan.

By the time the articles reached the Senate, Republicans increasingly accepted the idea that Trump may have withheld the aid in order to cheat, but they attempted to diminish the impact of that stunning notion by charging that the House had executed a shoddy, haphazard investigation and failed to prove the allegation.

This isn’t true. And it reflects a willful misunderstanding of the Constitution: To impeach is merely to accuse; it’s the trial in the Senate that is meant to prove or disprove the allegations.

And ultimately Senate Republicans came very close to admitting outright that the allegations against Trump are valid. They gave ground, finally relying —briefly —on the Alan Dershowitz defense, the bizarre notion that any act, even cheating in an election, is permissible if the president thinks his re-election is in the country’s best interest.

In the end, Sen. Lamar Alexander spoke for a lot of Republicans as he tried to rationalize his vote against allowing witnesses and documentary evidence: He admitted that Trump is guilty of the allegation, but he called the conduct “inappropriate,” resorting to a word popular among sexual harassers who wish to minimize their behavior while they attempt to apologize for it.

Inappropriate? Does this term accurately describe an attempt to swing an American election by the illegal act of withholding military aid from an ally who is crucial to our own security?

Jan. 31 was, indeed, a dark day: It represents the point where our capacity for outrage was at last fatally blunted by our exposure to so much that is outrageous.

John M. Crisp, an op-ed columnist for Tribune News Service, lives in Georgetown, Texas, and can be reached at jcrispcolumns@gmail.com.