In the last two decades, the work of turning excess woody material from the forest, and sawdust from mills, into pellets for fuel has boomed in the American Southeast. Several factories in Washington already turn forest slash into fuel for heating wood stoves.

But no manufacturer in the state has churned out pellets at the scale currently proposed for a wood pellet plant in Hoquiam.

The proposed facility in Grays Harbor County, after one already approved in Longview, would be among the first industrial-scale wood pellet manufacturers in the Pacific Northwest U.S., a prospect that has environmentally-minded locals — and others watching from the opposite corner of the country — wary.

After establishing across the Southeast and gaining a foothold in British Columbia, large pellet plants are creeping into Washington, drawn by overseas markets where governments are shifting away from fossil fuels and turning to wood, a renewable resource, instead.

The plants bring jobs and could fill an economic hole left by faltering pulp and paper mills that consumed extra wood and debris left over from the state’s logging operations.

The task for ORCAA — the Olympic Regional Air Quality Agency — is to issue an air quality permit to a pollution-emitting plant for which it has no precedent.

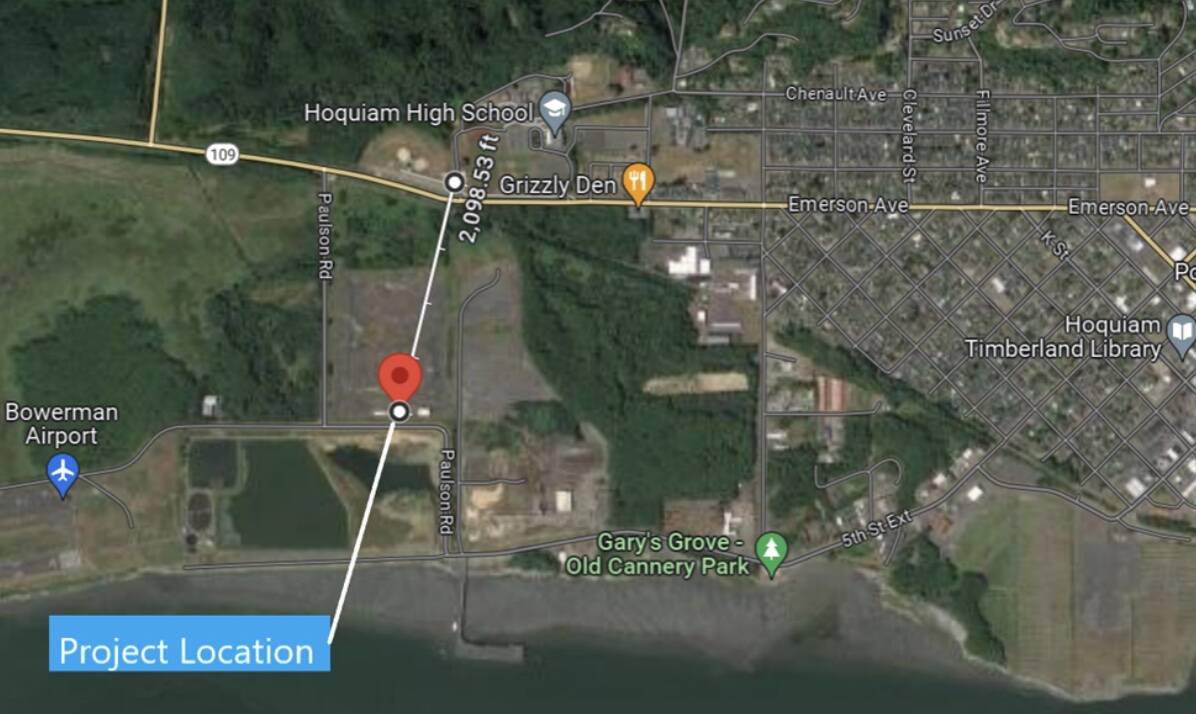

On Jan. 16 the agency hosted a public hearing in Hoquiam for a proposal from a company called Pacific Northwest Renewable Energy, which is seeking approval to build and operate a pellet mill at 411 Moon Island Road in Hoquiam, near the Port of Grays Harbor Terminal 3.

The company, PNWRE, submitted its application in July, proposing to build a plant, storage silos and a new conveyor on a 60-acre parcel located east of Bowerman Airport through a lease with the Port of Grays Harbor. The facility, capable of producing nearly 450,000 tons of wood pellets per year, would connect by conveyor to a nearby chip mill, Willis Enterprises, to access its ship loadout facility.

Wood pellets would then be exported, via vessel, to international markets, including Asia and Europe.

On Nov. 30, after three amendments to the application, ORCAA issued a preliminary decision to approve it. The most recent public comment period, and this week’s public hearing, garnered more interest than usual, said Jeff Johnston, executive director of ORCAA.

On Tuesday, members of the Grays Harbor Audubon Society expressed their concerns about noise and air pollution impacting the nearby Grays Harbor Wildlife Refuge, a sanctuary for migrating shorebirds and site of an annual festival. Others worried about the impacts on the complex of Hoquiam schools located about a mile to the north, and the communities beyond.

Liz Ellis, a member of the Aberdeen City Council, said she feared the plant would contribute to more bad air days downwind in Aberdeen.

“Grays Harbor County desperately needs well-paying jobs for our economy to thrive, and to put people to work, but not at the cost of pushing the metrics of poor health already among the highest among the highest in the state,” Ellis said at the hearing.

According to ORCAA, primary sources of pollution at the pellet plant would come from burning woody debris for heat and dust created from wood processing. For each source, the agency requires emission control technologies that reduce the actual amount of pollutants that reach the air.

Based on the plant’s potential to emit a certain amount of chemicals like carbon dioxide and particulate matter, ORCAA considers it a “major source” of emissions, although the projected emissions aren’t high enough to require a pre-construction permit from the Washington Department of Ecology.

But a group of environmental lawyers says PNWRE may have significantly underestimated the hazardous pollutants it will spew into the air.

On Jan. 8, two lawyers from the Southern Environmental Law Center sent a letter to ORCAA regarding the proposed plant in Hoquiam. Since 2017 the center has reviewed permits for more than 35 wood pellet plants in a dozen Southern states. According to the center, it has compiled a database of emissions tests from the smokestacks of wood pellet plants.

In its application, PNWRE estimated the proposed plant will emit 1.3 tons of Hazardous Air Pollutants (HAPs) each year — a projection the law center says is “deeply flawed and based on incorrect and/or outdated emission factors … factors that are not specific to wood pellet plants.”

“Recent stack tests and air permit applications that are specific to wood pellet plants show that a facility this size and with the controls proposed by PNWRE will emit at least 40 tons of total HAPs per year,” the law center states, calling for ORCAA to withdraw the application until the issues are addressed.

When asked how PNWRE reached its emissions calculations, the company deferred to the air quality agency.

“ORCAA will be responding to all the comments within the required time frame very shortly,” Kim Alexander, PNWRE’s vice president of operations, said in an email.

Lauren Whybrew, the ORCAA engineer assigned to the wood pellet plant’s application, said the agency’s job is to ensure emission estimates reflect the maximum potential to emit of each specific source.

“There’s a lot of back and forth before the preliminary determination is issued, questions of the applicant about the veracity of their (emissions) calculations,” Johnston, of ORCAA, said after Tuesday’s public hearing. “Those are definitely things that we’ve looked at. We’ve certainly, I think, heard some things here tonight that will cause us to look a little bit more carefully at some of those things. Based on the number of comments we’ve received that will likely take a few weeks and maybe longer to look carefully at these issues.”

Dan Nelson, a spokesperson for ORCAA, said there is no set timeline for responding to comments. After reviewing comments, he said, staff will draft a final determination on the application and present it to the executive director.

A bridge fuel

There are about 160 active wood pellet manufacturing facilities in the country, according to Biomass Magazine. The proposal for Hoquiam is on par with the scale of other industrial pellet plants in the U.S. It would have about seven times more capacity than a pellet plant in Shelton, which supplies wood for pellet stoves.

The facility would be Pacific Northwest Renewable Energy’s first pellet mill and first investment in the Pacific Northwest. The company lists a Massachusetts mailing address on official forms, but Alexander, the company’s VP, said Washington state will become its headquarters should construction of the pellet plant begin.

Alexander said the company’s leadership team has 50 years of combined experience in the biomass energy business.

Burning biomass — renewable organic material — is humankind’s oldest heat source. Modern bioenergy has been described as a “bridge fuel” from coal and gas to sustainable sources, according to a December 2023 paper from the University of North Carolina and the National Wildlife Federation.

The paper states that by burning wood instead of fossil fuels, countries can reduce the emissions they are required to report to global carbon accountants like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

As opposed to fossil fuels, biomass is renewable because plants absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as they grow; however, according to the UNC paper, burning wood releases approximately as much CO2 as coal.

In part, demand from overseas, mainly Europe, led wood pellet production in the Southeast U.S. to skyrocket in the 2010s. Asian markets across the ocean from the Pacific Northwest are also expected to grow.

“They’re classifying burning wood pellets as being renewable energy, and they’re sourcing it from a country that has great forest resources: the United States,” said Rita Frost, an advocate with the Natural Resources Defense Council, a Washington, D.C. based nonprofit.

Frost has worked on forest issues since 2015, when she lived in North Carolina and tracked the rise of wood pellet plants in the south. Now living in Eugene, Oregon, Frost is pushing back against big biomass as it moves into the Northwest.

Frost and the NDRC organized a Jan. 18 letter to ORCAA encouraging the agency to halt and reassess PNWRE’s pellet plant application. Signed by dozens of local and regional environmental groups, the letter expresses concerns about pollutants, noise, pellet storage and other environmental impacts, including the plant’s potential to increase logging.

But PNWRE states that it won’t cut trees to produce its product. According to Alexander, pellets are made from excess wood shavings produced by sawmill operations, and from slash and forest residuals generated by commercial logging and forest remediation activities. Alexander said all feedstock must originate from certified sustainable sources, including the Forest Stewardship Council and the Program for the Endorsement of Forest Certification.

Local demand for woody biomass helps drive the removal of extra branches and debris left on the ground after a logging operation, which helps reduce wildfire risk, said Cindy Mitchell, a spokesperson for the Washington Forest Protection Association, a trade association that represents private forest landowners. Mitchell said pellet mills could fill the market hole left by declining pulp and paper mills, citing the August closure of the century-old Tacoma Paper Mill.

“All parts of a tree need a market,” Mitchell said. “If a piece of it goes, then it really challenges the whole infrastructure. Any time I hear of a market for parts of a tree, especially when it comes to the waste product, it’s a good thing.”

Pacific Northwest Renewable Energy’s proposed plant would create 53 new jobs and generate $155 million in new capital investment, according to a news release from the Department of Commerce. In April, the state economic agency awarded the company a $200,000 grant funded through a program designed to boost manufacturing jobs in Washington state.

Last year the state Legislature passed a bill introduced by Rep. Steve Tharinger (D-24) that gave tax breaks on sales of wood waste and residuals, in an effort protect jobs and comply with the state’s 2045 deadline for fossil fuel-free electrical generation.

Contact reporter Clayton Franke at 406-552-3917 or clayton.franke@thedailyworld.com.