At the conclusion of the state legislative session in late April, Jerry Cornfield, The Herald’s political columnist and legislative reporter, mused about what was left on Gov. Jay Inslee’s to-do list now that long-sought action on a carbon cap-and-invest system, a clean-fuel standard and a capital gains tax had all passed and were ready for his signature.

“With no outstanding legislative goals of note, he’s going to be bored,” Cornfield wrote.

But Inslee may have created a new — and potentially daunting — to-do list for himself following partial vetoes to the cap-and-trade and clean-fuels legislation that have arguably soured his relationships with lawmakers from his own party and with the state’s Indigenous tribes.

Lawmakers from both parties took offense when Inslee used a line-item veto to remove a provision in the legislation that lawmakers had negotiated to win its passage that required adoption of a transportation package and a gas tax increase of at least 5 cents by the bills’ effective date of 2023. Inslee signed the legislation he had long sought, but removed the lawmakers’ trigger, not wanting to risk implementation of the climate legislation on the whims of lawmakers to adopt a tax increase and a list of transportation projects.

Lawmakers’ criticisms followed quickly, among them:

“This sets a chilling precedent and poisons the well for all future negotiations on virtually any tough issue,” state Sen. Mark Mullet, D-Issaquah, said in a statement. “When it comes to the governor’s top priorities in the future, he should expect a more hostile Legislature if this is the path he wishes to take.”

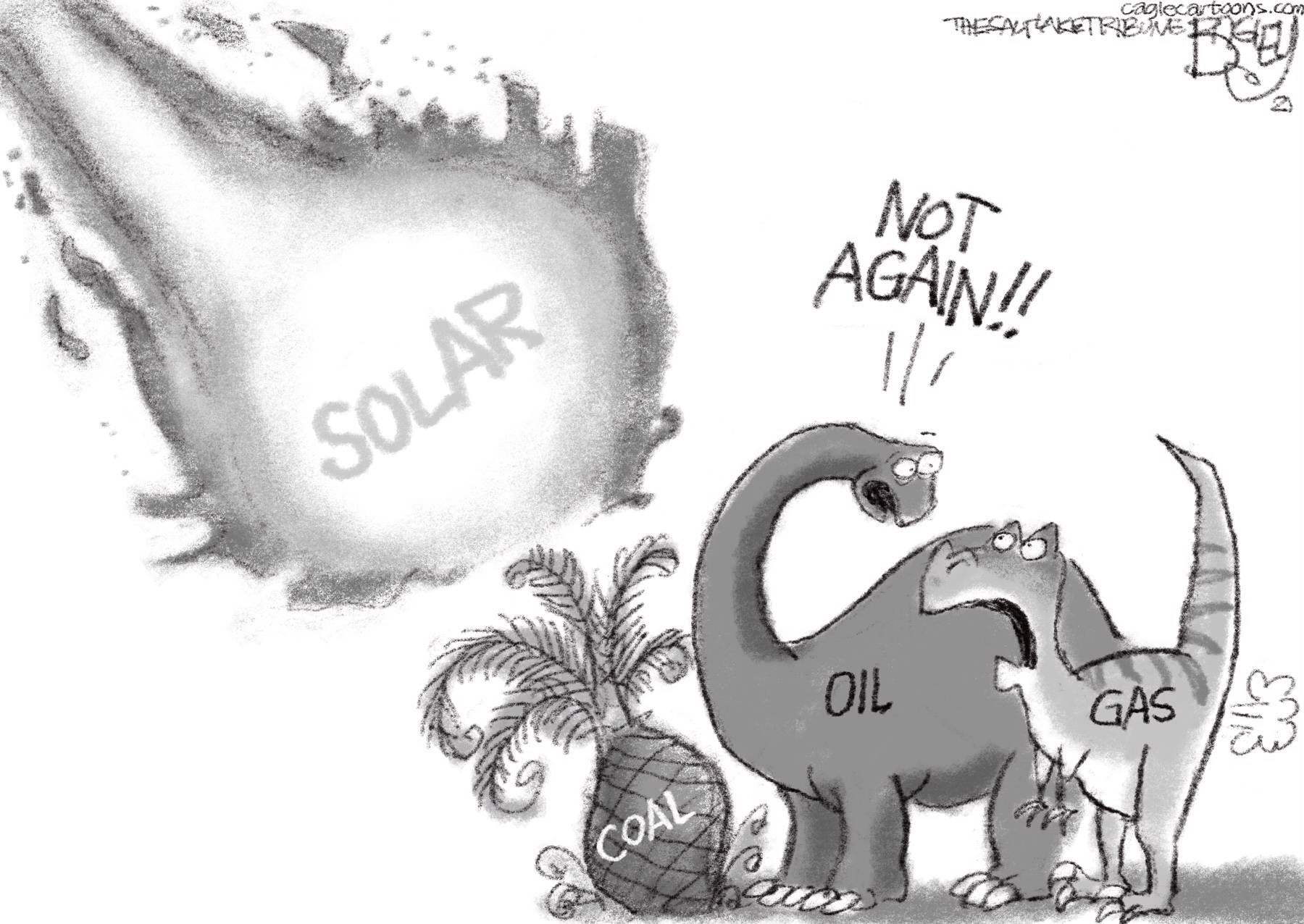

But the reactions of lawmakers were mild in comparison to that of Indigenous tribes within the state, regarding a concurrent veto of a section within the Climate Commitment Act (Senate Bill 5126) — again negotiated and agreed to by lawmakers in consultation with tribes — that sought to recognize tribal sovereignty by seeking consent for proposed development projects affecting tribes, such as solar energy projects that could have impacts on areas used for food-gathering, burial sites and other sacred grounds.

“Jay Inslee committed the most egregious and shameless betrayal of a deal I have ever witnessed from a politician of any party, at any level,” said Fawn Sharp in a statement following the veto and reported in The Seattle Times. Sharp is vice president of the Quinault Indian Nation and president of the National Congress of American Indians, which represents 500 tribes in the United States.

Robert de los Angeles, chairman of the Snoqualmie Tribe, was as blunt: “To plainly speak the truth, Gov. Inslee used, exploited and betrayed Tribal Nations in order to pass his climate change bill,” de los Angeles said in the same news release.

“The only thing I will ever agree with Donald Trump about is that Jay Inslee is a snake,” Sharp concluded in her release, a mic drop that played on the animosity between the governor and the former president.

That harsh criticism of Inslee coming from traditional allies — and Sharp’s “snake” attack — was noted by at least one national media outlet. The National Review commented last week: “What you’re left with is yet another egregious example of how even the most progressive officials, when pressed to relinquish a modicum of their government’s power in the name of righting institutionalized wrongs of colonialism, continue choosing power over Indigenous rights.”

Inslee, in his signing statement, justified his veto as necessary to protect the current “government-to-government approach” and the relationships between the state and the state’s 19 Indigenous tribes. In the same statement — if not the same breath — he also requested more negotiation with tribal leaders to develop an improved consultation process for projects, in lieu of the tribal consent that lawmakers had written into the legislation.

As well, Mike Faulk, an Inslee spokesman, said in an email to the Times that the vetoed section “was written so broadly that it would have made it possible to challenge just about any related project anywhere in the state.”

Like the legislative language that tied the climate legislation to passage of a transportation package and its funding, Inslee’s veto of the tribal consent provision sought to remove any potential hurdles for actions on reducing carbon emissions and moving forward with renewable energy projects.

There would be risks with both, clearly. Even acknowledging this year’s extremely productive session, particularly on environmental issues, the Democrats maintain narrow majorities in the House and Senate, and there are no guarantees that a transportation package — and the increases of taxes and fee necessary to fund it — will be adopted in the next few years.

Likewise, one or more tribes could say no to a project, even something as worthy as a solar energy farm. Yet, as sovereign nations, who either hold long-occupied lands or maintain cultural rights to their use, they should retain that right — as a government as equal in stature to the state itself — to say no. As well, a denial isn’t always the final word, as it can lead to further negotiations that can find compromise.

Inslee earned praise during his abbreviated run for president last year by putting an almost exclusive emphasis on climate issues, attempting to pull his fellow Democratic candidates into joining him in that focus. His commitment to reducing carbon emissions and addressing the effects of climate change will likely be the most notable legacy of his three terms in office.

But in seeking more certainty for his climate goals at any cost, Inslee has now shaken his relationships with Democratic lawmakers and the state’s Indigenous tribes, partners who shared his commitment to those goals. And he has likely complicated future negotiations with lawmakers and the tribes on a range of issues.

The governor no longer need be concerned about how he’ll occupy the time remaining in his term. He can add two major infrastructure projects to his list: rebuilding the bridges he just burned.

The Daily Herald is a newspaper owned and published by Sound Publishing, Inc., which also owns The Daily World.