By Doyle McManus

Los Angeles Times

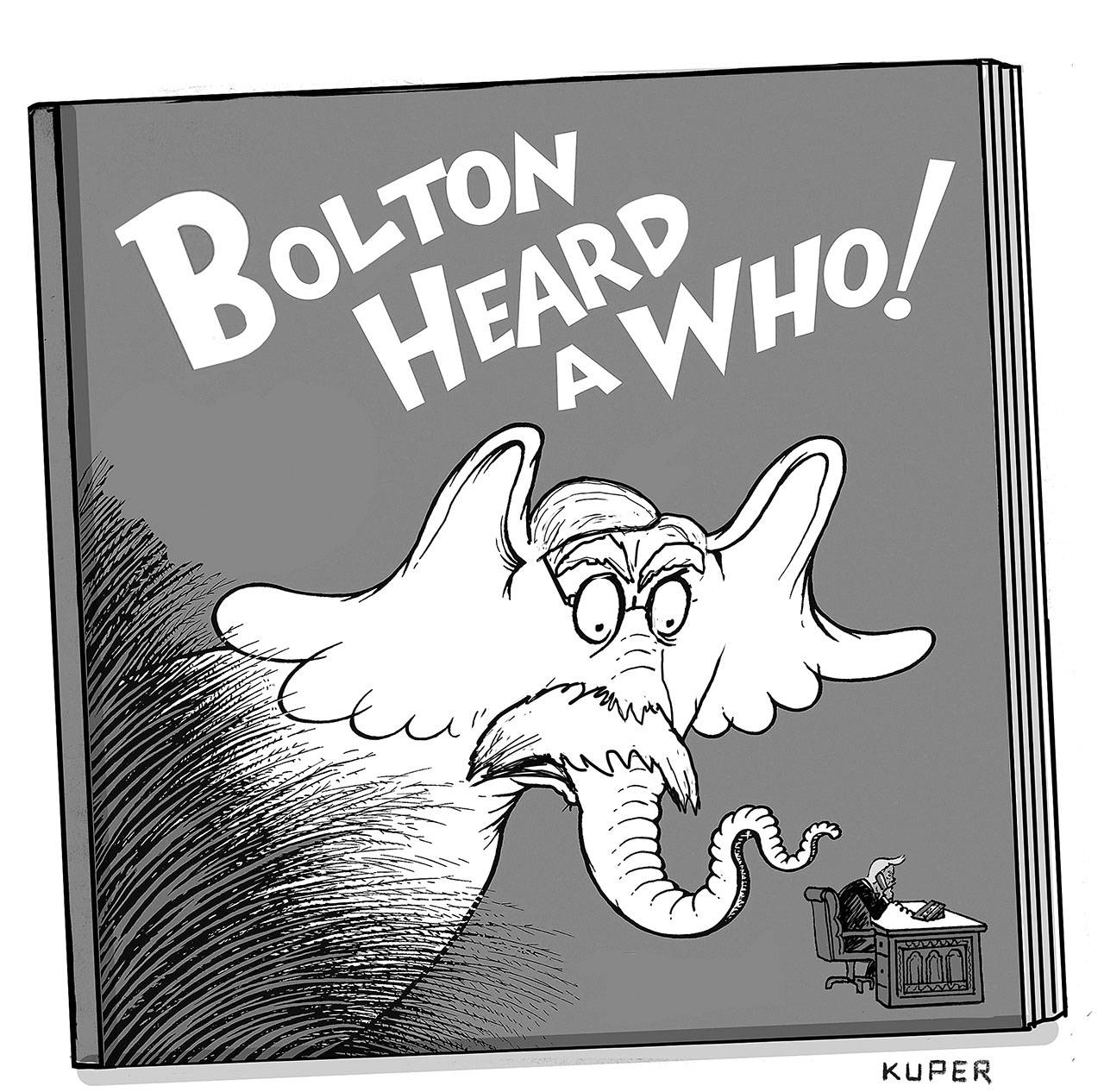

The most striking thing about John Bolton’s long and furious book about his 17 turbulent months as President Donald Trump’s national security adviser isn’t his revelation that Trump is an ignoramus. We knew that.

Nor is it his portrait of a president who admires dictators more than democratically elected leaders. We knew that too.

It’s not even news that Trump has tried to use foreign policy to help his reelection campaign. Trump was impeached for that.

The value of Bolton’s book, for those with the courage or stamina to plow through its 494 pages, is his fly-on-the-wall narration of Trump’s collision with China.

On the most important foreign policy challenge of our time, Trump turns out to have almost no strategy at all — only a conviction that by slapping tariffs on Chinese goods, he can force Beijing to buy more U.S. soybeans and help him win farmers’ votes in November.

His administration’s official trade policy, drawn up by chief negotiator Robert Lighthizer, includes a long list of goals: an end to Chinese government subsidies of key industries, an end to the theft of U.S. intellectual property, and more.

But when Trump met with Chinese President Xi Jinping at the G-20 summit in Argentina in December 2018, he preemptively reduced all those demands to just one.

“Trump asked merely for some increases in Chinese farm-product purchases, to help with the crucial farm-state vote,” Bolton wrote. “If that could be agreed, all the U.S. tariffs would be reduced. It was breathtaking.”

Then comes the punch line: “Trump asked Lighthizer if he had left anything out.” Uh, yeah.

The president wasn’t shy about his motive.

“Make sure I win,” he told Xi, according to an account in Vanity Fair of Bolton’s manuscript before the White House demanded changes, claiming Trump’s comments were classified.

“I am hard-pressed to identify any significant Trump decision during my tenure that wasn’t driven by re-election calculations,” Bolton wrote.

The United States has many problems with China beyond trade — but in Bolton’s telling, none of them seemed to interest the president much.

On Beijing’s creeping takeover of the South China Sea, there’s hardly a word. When China cracks down on democratic freedoms in Hong Kong, the president backs his friend Xi. Trump considers Taiwan, a democratic outpost that China wants to take over, little more than an annoyance.

And it gets worse. The president told Xi that he understands why China decided to build concentration camps to detain more than 1 million of its Uighur Muslim citizens. “Trump thought (it) was exactly the right thing to do,” Bolton observed.

The controlling principle appears to be staying on Xi’s good side, the better to nudge him toward those all-important soybean purchases.

When ZTE, a Chinese telecom company, gets caught violating U.S. sanctions on Iran, Trump offered to intervene. (“Xi replied … that he would owe Trump a favor.”) Thanks to the president, the company’s proposed fine was reduced.

When the Justice Department sought to prosecute an executive for Huawei, a telecom giant the U.S. considers an arm of Chinese intelligence, Trump again offered to help out. Bolton and other aides made sure he didn’t.

Bolton can barely hide his disdain at what he calls “obstruction of justice as a way of life.”

Trump has a favorite boast: “Nobody has been tougher on China than me.” And he has been tough, at least when it comes to rhetoric and tariffs — although his frequent claim that he’s the first president to impose tariffs is false.

Parts of the Trump administration have been tougher than he was. Lighthizer has pursued ambitious long-term goals on trade. The National Security Council designated China a major U.S. adversary. The Pentagon runs often-risky air and sea patrols in the South China Sea. Trump has undercut those measures with his impulsive concessions to Xi.

The president says Bolton’s book is “made up of lies and fake stories,” but Bolton isn’t the only one who has offered this critique. It’s one of the reasons James N. Mattis resigned as secretary of Defense in December 2018, warning that Trump wasn’t “clear-eyed about … strategic competitors.”

Tough rhetoric isn’t a strategy — especially when it’s combined with desperation to strike a quick deal before the next election.

Besides, China hasn’t even fulfilled its promise to buy more soybeans. In the first four months of 2020, Beijing bought less than $5 billion worth of U.S. agricultural goods, a pace far short of its pledge to spend $36.5 billion this year.

So if Trump wants to make China policy a cornerstone of his re-election campaign, he’s got a problem. Bolton’s book, clearly written in anger (and for a reported $2 million advance), has been a gift to Joe Biden.

With his campaign losing ground, Trump may fall back on one of his main themes from 2016 — that only a smart businessman who’s not from Washington can whip Washington into shape.

Only that claim is tattered, too. One measure of any executive is how successful he or she is at hiring people.

Trump, by his own admission, has hired a brilliant string of world-class advisers — ”only the best people” — only to discover they were dolts.

Bolton, he now says, was “wacko” and “a dope.” Mattis was “the world’s most overrated general.” His first secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, turned out to be “as dumb as a rock.”

Future Cabinet picks might be better off following First Lady Melania Trump’s example: Negotiate a prenup.

Doyle McManus is a columnist for the Los Angeles Times. Readers may send him email at doyle.mcmanus@latimes.com