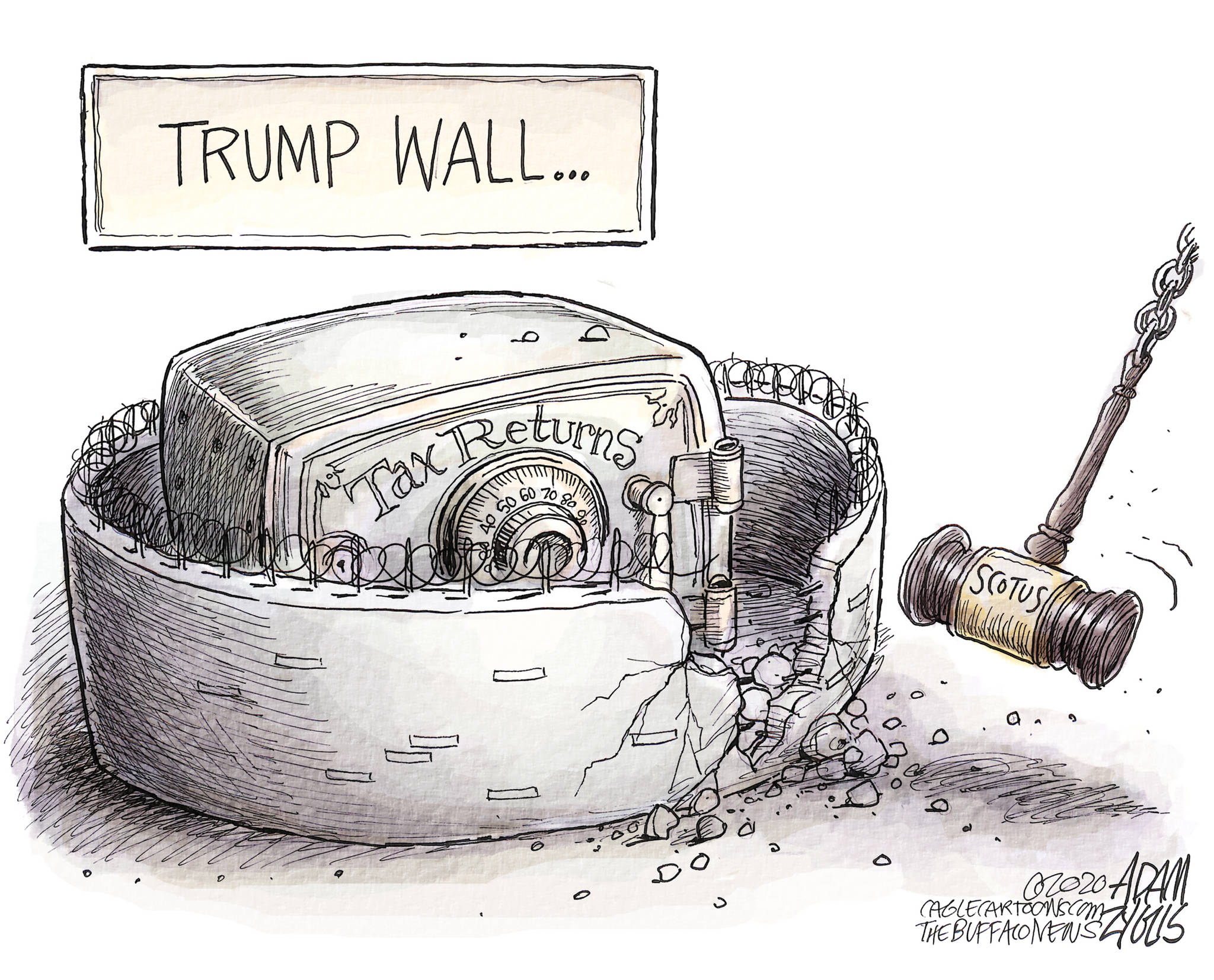

The dual opinions that the Supreme Court issued Thursday concerning the release of President Donald Trump’s financial records amount to a sound defeat for the White House’s claims for aggrandized executive power.

The court refused to break new ground to alter the constitutional power of the executive branch or the balance between it and Congress. Along the way, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. demonstrated extraordinarily strong and effective leadership of the court that bears his name.

Roberts managed to achieve what has to have been his primary goal in Trump vs. Vance and Trump vs. Mazars, the pair of closely watched cases on the question of whether the president can refuse subpoenas: He got the justices to speak in a nearly united voice. In each case, the vote was 7-2. Two 5-4 opinions, reeking of partisanship, would have been terrible for the Supreme Court’s institutional stature and the nation’s confidence in the rule of law.

To achieve his ends, Roberts marshaled compromises between the often warring wings of the court. His majority decisions now join with unanimous decisions in the Watergate era’s U.S. vs. Nixon and during the impeachment of Bill Clinton. In both those instances, when presidents tried to resist answering to Congress and the law, the Supreme Court decisively rejected claims of overweening authority.

In Vance and Mazars, the White House argued for an extra measure of solicitude for the executive branch, to protect presidents from supposed harassment and overreach.

In Mazars, in which three House committees sought personal financial records of the president, any such ruling would have effectively put an unprecedented judicial thumb on the scale against the legislature and its powers. (It also would have dovetailed with the political goals of conservative lawyers who for the last 40 years have tried to bolster the executive against the power of the legislature.)

The court, and Roberts especially, would have none of it.

In Vance, which concerned the Manhattan district attorney’s attempt to subpoena Trump’s personal financial records in a criminal case, the justices likewise unanimously rejected (with dissents by Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito on other grounds) Trump’s bid for solicitude, this time in the form of a wacky assertion of “temporary immunity” from criminal processes. Any such privilege would run directly across the grain of constitutional history, which Roberts laid out in detail, going all the way back to Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton (and adding to the shoutouts the hit Broadway play received in court decisions this term).

The Vance opinion makes clear that existing safeguards against the use of criminal processes to harass, rather than investigate, a criminal defendant provide ample protection even for presidents.

Most important, Roberts refused to take what would have been a plausible step: requiring a state prosecutor to make some showing of “heightened need” in order to subpoena a sitting president. Such a result would have placed the president, however slightly, above the law.

The Mazars case reflects a greater degree of compromise and nuanced persuasiveness on Roberts’ part. You can almost picture the chief justice at conference announcing dual principles to get his 7-2 majority, one to please the liberal wing, the other to mollify at least Brett M. Kavanaugh and Neil M. Gorsuch.

He again began the opinion with a long historical discourse, noting how unusual it was for disputes between Congress and the president to wind up in court, rather than getting settled in the “hurly-burly give and take” of politics. (One senses here a mild chiding of both branches —I would argue the president more richly earned it —for failing to play nicely in the constitutional sandbox.)

The Mazars decision pointedly rejects the notion that the House of Representatives must meet a heightened standard such as a “demonstrated specific need” to get information out of the president. But there follows a section, designed to attract the conservatives, that sets out an elaborate four-part test for assuring that due weight is given to separation of powers concerns when Congress subpoenas the president.

It almost seems to make the president a special case, but, critically, a close read of the four elements reveals them to be essentially exacting versions of familiar standards: Carefully assess whether legislative purpose warrants the info; be sure the subpoena is no broader than necessary; be attentive to the nature of Congress’ evidence that there is a valid legislative purpose; be careful to assess the burdens on the president.

The decision remands Mazars to the lower courts to do all that painstaking reviewing. And that will take time. The practical upshot is that before the election neither Congress nor the public is likely to see what the House subpoenaed. Much the same is true in the Vance case, but in that instance, Trump’s record will remain out of view primarily because the records sought will be covered by grand jury secrecy.

The Vance and Mazars decisions will go down in concert with the other historical episodes Roberts set out as a rejection of a president’s invitation to put himself above the law. At the same time, these are conservative rulings. They prescribe a close, careful look at current law; they don’t break new ground. In the context of a splintered court, a roiled presidency and white-hot disputes involving fundamental questions of executive power, not at all a bad day’s work for the chief.

Harry Litman is a former U.S. attorney and the host of the podcast “Talking Feds.”