By Michael McGough

Los Angeles Times

Reporters who cover Congress are rightly protesting restrictions on press coverage of President Trump’s Senate impeachment trial. In a letter to Senate leaders, my Los Angeles Times colleague Sarah D. Wire, who chairs the Standing Committee of Correspondents, objected among other things to a proposal that reporters be confined to “pens” preventing them from “freely accessing senators as they come to and from the chamber.”

Echoing that complaint, the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, joined by 57 news organizations, sent a letter to the Senate on Thursday night asking it to reconsider the restrictions. The letter says reporters “must have the ability to respond quickly to rapid developments and need reasonable access to lawmakers who wish to speak to the press.”

Whatever else this controversy demonstrates, it undermines the notion that senators are “jurors.” Not many reporters would try to interview actual jurors during the progress of, say, a sensational murder trial, and the jurors would be under orders not to talk to them.

This is from a handbook for reporters prepared by the District of Columbia Courts: “Courts generally do not prohibit the press from talking to jurors after the trial ends. Judges, however, will order jurors not to talk to the press while deliberations are ongoing, or remind them that what takes place in the jury room is confidential. Jurors, of course, can choose whether to speak with reporters after the trial has concluded.”

Senators in an impeachment trial are under no comparable gag order, although some will choose not to talk to the press. (To aid reluctant senators in fending off inquiries, Capitol Police have provided them with cards that say “Please get out of my way” and “You are preventing me from doing my job.”)

It’s not only in their ability to speak to reporters that senators differ from jurors in a criminal trial. Prospective jurors can be disqualified if they have connections with the defendant. Obviously this rule can’t be applied to an impeachment trial, in which many of the senators will be political allies or opponents of the president. In his classic study of impeachment, the late constitutional scholar Charles L. Black Jr. wrote that “it cannot have been the intention of the Framers that this rule applies in impeachments, for its application would be absurd.”

Does that mean senators should just vote their political allegiance and ignore the evidence?

Not at all. Black wrote: “In voting on each article of impeachment, each senator, acting in a capacity combining those of judge and jury, is registering his best judgment ‘on the facts’ and ‘on the laws.’ This means that he is answering two questions together: ‘Did the president do what he is charged in this article with having done? If he did, did that action constitute an impeachable offense within the meaning of the constitutional phrase?’”

(Black also emphasized that senators must confine their judgment to whether the president committed the specific offenses cited in the articles, which means that senators shouldn’t vote to convict Trump for his attempts to thwart special counsel Robert S. Mueller III’s investigation or some other real or imagined corrupt conduct.)

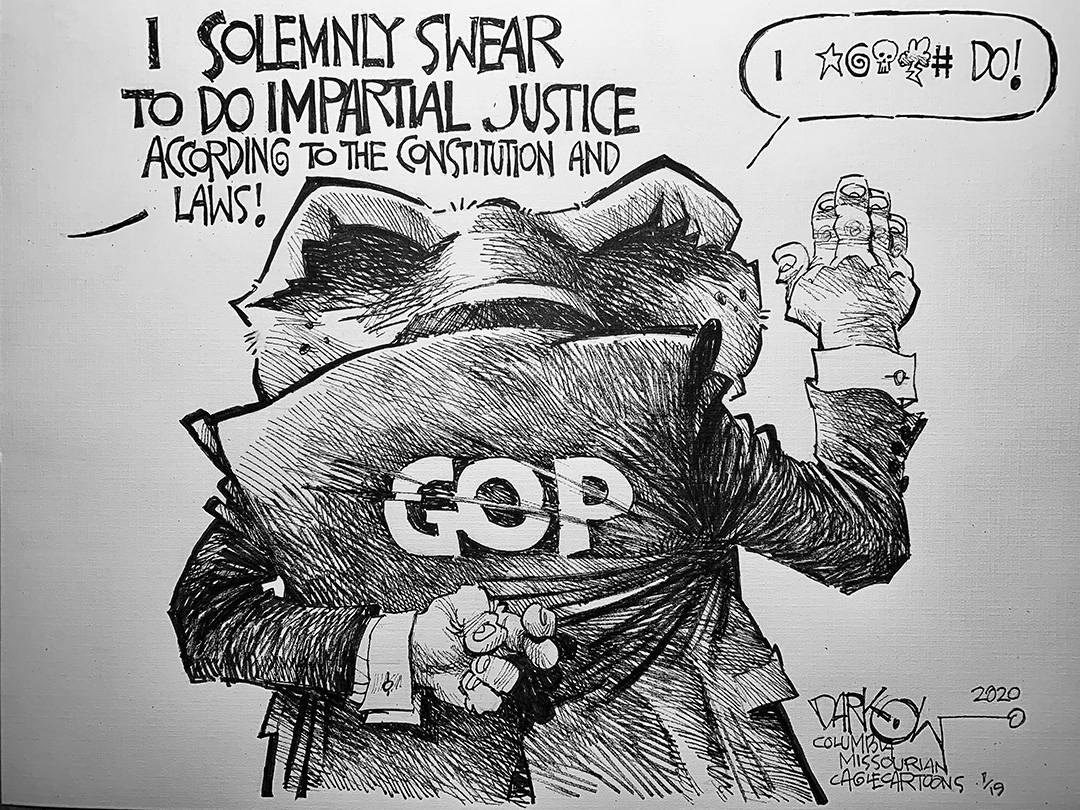

So senators aren’t jurors —which is why it’s acceptable for reporters to ask them questions and for the senators to reply —but neither are they free to vote their partisan loyalties or declare in advance, as Sen. Lindsey Graham did, that “I have made up my mind.” Senators take an oath to “do impartial justice according to the Constitution and laws, so help you God.” It ought to mean something.

Michael McGough is the Los Angeles Times’ senior editorial writer, based in Washington, D.C.