By Bruce Ackerman and Ro Khanna

Los Angeles Times

Source: McClatchy

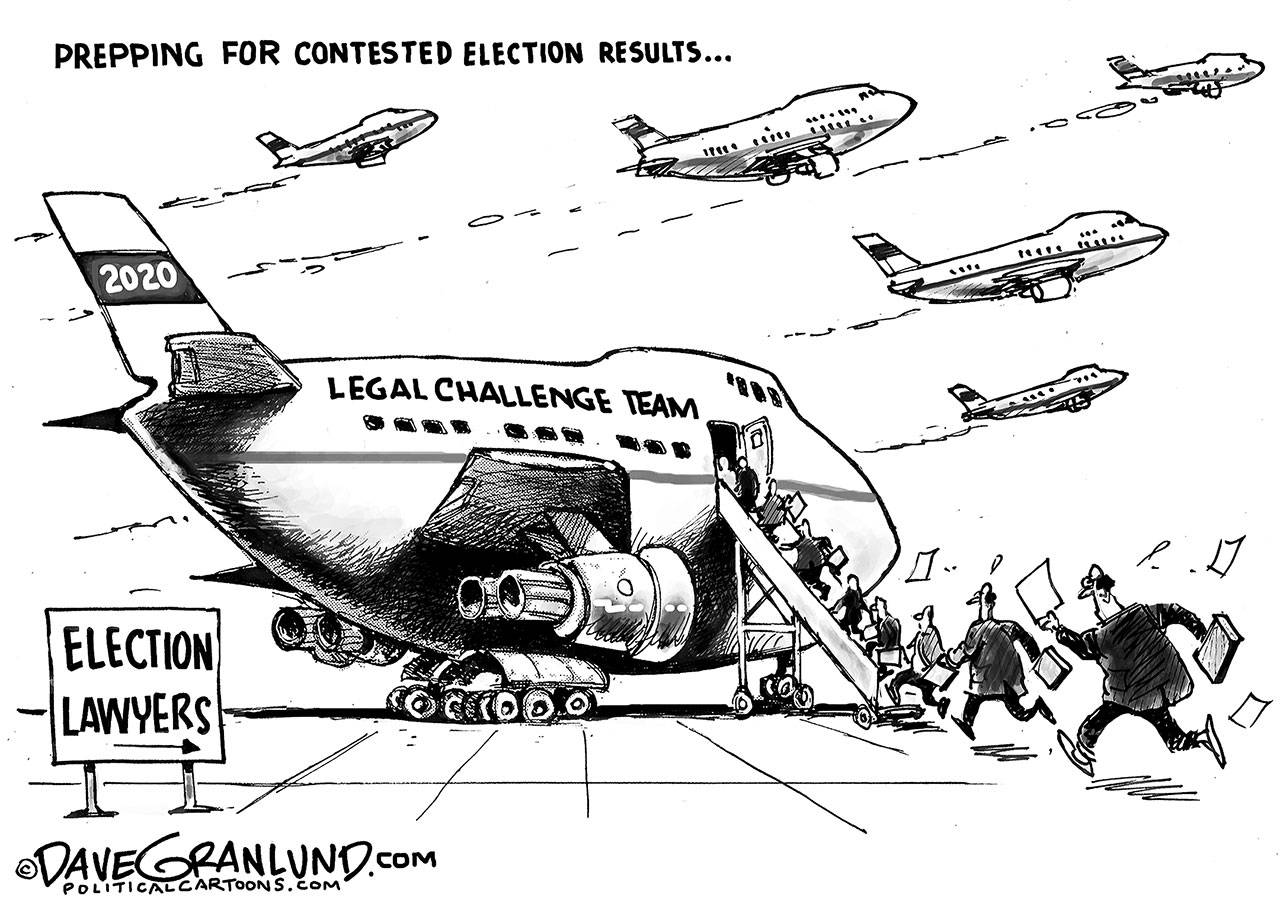

President Donald Trump’s claim that only “a rigged election” will yield a Democratic victory poses the risk of a constitutional crisis far beyond anything Americans witnessed in Bush vs. Gore, when the Supreme Court precipitously intervened to award the 2000 election to George W. Bush. Two decades later, the best way to confront the looming crisis is to enlist the Supreme Court in a very different fashion — by creating a special commission, headed by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., to oversee the disposition of any disputed state election results.

To understand why such a commission is needed, begin with the Founders’ elaborate rules for verifying and officially determining who will be president and vice president.

After a presidential election, when Congress reconvenes early in January, the nation’s 435 representatives and 100 senators are required to meet in the House chamber in a special joint session. The Constitution designates the sitting vice president to preside over the proceedings — in 2021, Mike Pence will be in the chair.

The process is rarely dramatic. The Constitution instructs the vice president to “open all the certificates” —the reports of the electoral college vote counts — submitted by the states. Beginning with Alabama and ending with Wyoming, each result is announced and the joint session is asked to approve it (the House members vote on the presidential certificates; the Senate votes on the vice presidential counts).

However, there is an exception to the general rule. Precedents established by Thomas Jefferson in 1800 would permit Pence to invalidate a particular state’s electoral returns on the grounds that the underlying vote-count was generated in an illegitimate fashion — that it was rigged.

Pence could refuse to allow the House or Senate to consider a state certificate that he found fraudulent and eliminate its electoral votes from the overall tally. That would reduce the number of electoral college votes required for a majority. If Pence used his prerogative in a partisan manner — for example, invalidating close results that favor Biden, but accepting those that favor Trump — he could mathematically upend the overall election.

If that seemed likely to happen, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi could play some legal and political hardball of her own. She could refuse to hand over the gavel to the vice president when Pence arrived in the House chamber to call the special January joint session into existence. That would make it impossible for Biden or Trump to claim the authority to be sworn in as president, and according to the Presidential Succession Act of 1947 —spearheaded by President Truman — it is the speaker who is third in line if neither the president nor the vice president can serve. Pelosi could forestall a handoff of the presidency to Trump by becoming “acting” president herself.

Either of these courses of action — Pence interfering with the election results, Pelosi refusing to allow Pence to call the joint session — would provoke political chaos, street demonstrations and even violence as the nation approached “noon on the 20th day of January” — the moment when the Constitution explicitly states that term of the “current President and Vice-President shall end.”

Given this grim prospect, the vice president and the speaker should publicly pledge that they will not engage in such partisan warfare. But Congress would be wise to act now to prevent the passions of January from spinning out of control.

The disputed presidential election of 1876 serves as a crucial precedent. It pitted Democrat Samuel Tilden against Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and involved contested election returns from several southern states. Rather than relying on the usual joint session, Congress delegated the job of resolving the controversies to a special commission — five Supreme Court justices, five senators and five House members. Tilden, a statesman, accepted their decision (with the justices playing the decisive role) to grant the presidency to Hayes.

For the 2020 election, Congress should immediately create a commission similar to the Tilden-Hayes panel. In this case, the right makeup would be five Supreme Court justices — two liberals and two conservatives, with Roberts as chairman. If the commission began monitoring the electoral process now, it could make fact-sensitive judgments on the accuracy of state vote counts come January. Pelosi and Pence should make clear their intention to abide by the decisions reached by the commission.

During the last few months, the Roberts court has frequently demonstrated a capacity to transcend the partisan divide and issue opinions that gained the broad support of a strong majority of justices. There is good reason to believe that a Roberts-led commission, backed by career professionals in the Department of Justice, would act with the same sense of responsibility in resolving a contested election.

Given the 2020 election’s high stakes, the probable increase in mail-in balloting amid the coronavirus pandemic, and the president’s claims about rigged results, the creation of a Roberts commission is the best way to assure that the United States can avoid electoral chaos that could be devastating to our democracy.

Bruce Ackerman, a professor of law and political science at Yale, served as a representative of Al Gore in Florida during the 2000 election crisis. Rep. Ro Khanna, D-Calif., is the first vice chair of the Progressive Caucus in Congress.