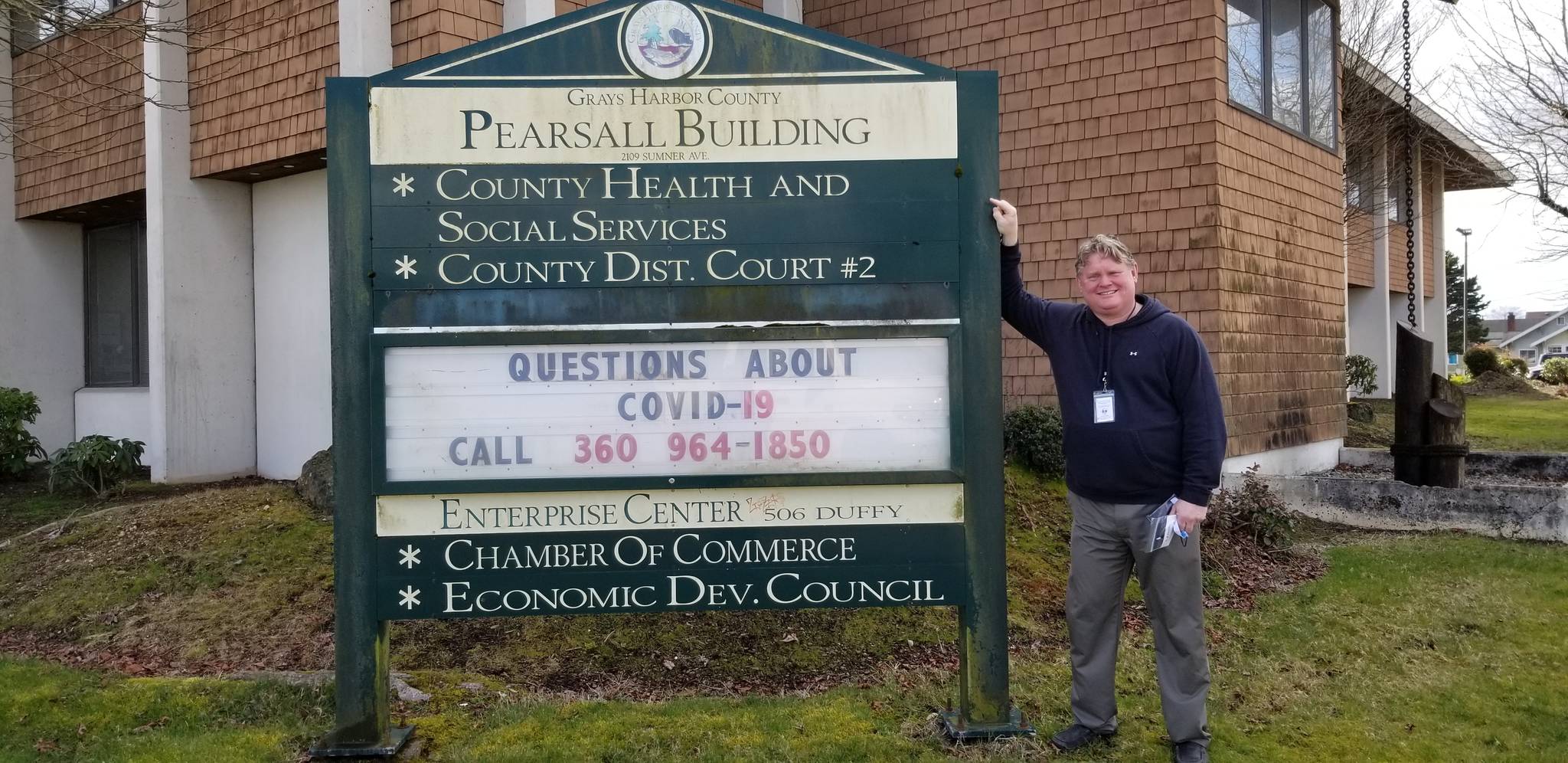

Just two weeks into his new job as director of Grays Harbor County Public Health & Social Services, Mike McNickle has plenty on his plate. On the public health side, there’s the pandemic. And on the social services side, he’s getting up to speed on the county’s response to homelessness and its handoff of a controversial needle exchange program to a non-profit agency.

McNickle takes over for Karolyn Holden, who resigned effective at the end of the year to take another public health job. Before coming here, McNickle was director of Clatsop County Public Health in Oregon, directing COVID response there. Grays Harbor county commissioners hired him in February.

On the county’s COVID-19 response, McNickle said he’s getting up to speed real fast and will become the local Incident Commander for the public health department’s role in the Incident Management Team beginning April 1. McNickle himself had COVID-19 last summer. His symptoms were mild, but it was a lesson in how easily it can be caught, he said.

McNickle grew up in the Bremerton area, he attended Western Washington University and Washington State University. “Go Cougs!” he said during a phone interview earlier this week. He also has a doctoral degree from Walden University, focusing on public health.

He’s lived in the region most of his life, his first job was at the Kitsap County Public Health Department then he worked for a couple of counties in Oregon. After seven years in Astoria working for Clatsop County, McNickle spotted the Grays Harbor opening and, with family living in the Olympia area, he said it was a perfect fit.

He jumped right into some of the “low hanging fruit issues” as he calls them, things like homelessness.

“We’re never going to solve the homeless issue in one silo, it’s on a spectrum. And it’s a long term goal, it’s not a short fix. So, you know, the longer I’m here, the more I can work on it,” says McNickle. He’s had a longstanding interest in finding solutions for those experiencing homelessness.

He envisions a system with many approaches, “where if someone is homeless, whether it be because of bad debt, or they had an accident, or they had something else happen, or they have an addiction issue, whatever the issue may be, not every single person — just like in medicine or any other thing — every solution requires that particular person to be set up with the right services.” His goal is to make a series of services available that captures the majority of folks who are willing and able to be treated for the spectrum of possible causes of homelessness, including mental health and addiction.

McNickle said that in Astoria there were groups of homeless people who could not be reached without services such as low-barrier shelters, needle exchange, and naloxone distribution. Naloxone, also called Narcan, is an opioid overdose reversal drug that binds to opioid receptors and can reverse and block the effects of opioids during an overdose.

“We had a number of the folks who had either addiction or mental health issues or both. But there just (are) not enough slots in the mental health system for these folks,” recalls McNickle. He said some people would refuse services even if they were available. He said it’s a frustrating situation for people trying to help, “and if they’re not a danger to themselves and others, how do you reach those people?”

“So like I said, there’s not a one size fits all, that’s not possible,” said McNickle. He uses the example of CARES act grants which are designed specifically to keep people from living on the streets, regardless of barriers. But the director adds that, “stable housing has got to come with those wraparound services, because their mental health and addiction services have got to be addressed at the same time, otherwise, they will fail.”

The county has operated a needle exchange program for several years, but county commissioners, on a 2 to 1 vote, recently voted to end it, effective at the end of the month. The service will continue, but it will be managed by the non-profit Willapa Behavorial Health, which will receive grant funding that had gone to the county.

On needles and the exchange services, McNickle says the needles are the least important part.

“The most important part is the saving of lives, and then referral to additional services when those people are ready. Those are the two missions of a syringe exchange program.” says McNickle. He doesn’t see an issue with Willapa Behavioral Health taking the needle exchange program over. He adds, “no matter who’s doing it, as long as they make sure that the folks who are using have the naloxone and know how to use it to save themselves and others who may be using around them. That’s the key.”

McNickle says the other important part of a needle exchange program is being there when those addicted are ready to go into rehab, “that we have a facility ready at that moment that they can go in and start that rehab.”

The doctor says the evidence-based program is the best way to get people into rehabilitative and technical services. He said it’s always difficult to reach intravenous drug users, “there’s a lot of stigma and shame that goes along with being a heroin user or any methamphetamine, whatever it is.” McNickle says the state of that shame is a serious barrier. Programs like the needle exchange build trust. He says the hope is “that when they decide they need to make a change, they trust that person will actually care for them to make sure they’re taken care of and get to the right place.”

McNickle says going without services like the needle exchange program would set the county back to where it was before 2004, “with overdoses going up, communicable disease rates rising, and you’ll have a lot more folks who are going to be going to the emergency department for things like skin conditions or endocarditis, or cellulitis. And those things are horribly expensive.” He notes that most serious I.V. drug users are also unemployed or without health insurance. “So they’re getting social services at the cost of the taxpayer. And five days in an ER with endocarditis is $100,000. For $100,000 you can do a lot of treatments, and naloxone distribution.”

Regarding fentanyl on the Harbor, McNickle said health officials testing contraband are starting to see most I.V. drugs laced with fentanyl, and are warning users of those drugs that the mix could kill them. He said that in Astoria they documented over 100 people saved through the Naloxone program. However, the fentanyl is so strong that first responders are having to use up to four doses in some cases to bring a person back from an overdose. These types of rescue are becoming more common because of the fentanyl. A Hoquiam teen recently ingested half of a pill suspected to include fentanyl and Hoquiam police had to use three doses of naloxone.

McNickle supports the naloxone distribution. He adds, “I know that the commissioners are strong supporters of Narcan or Naloxone distribution and training. I don’t think that would ever go away.”