KANSAS CITY, Mo. — “My family and friends … My family and friends …”

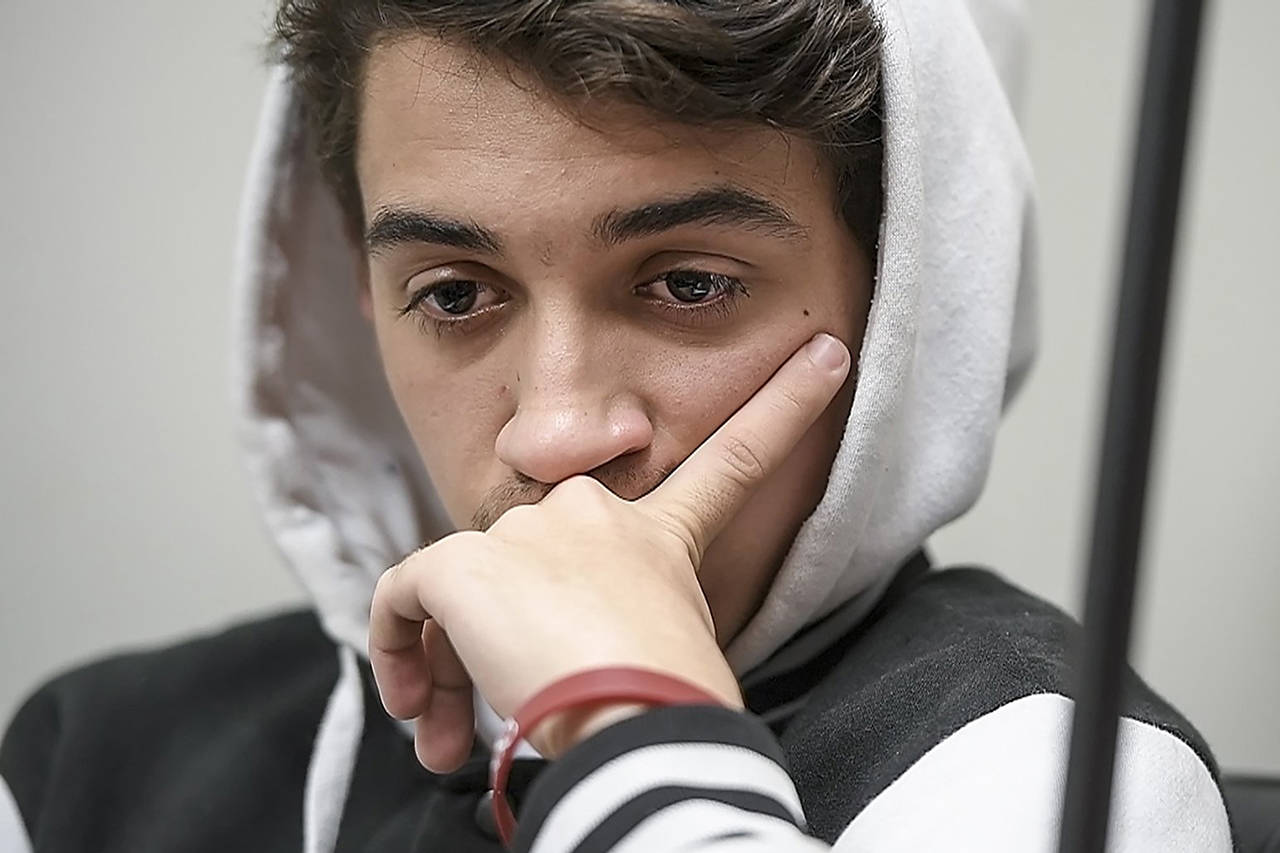

Sixteen-year-old Levi Baehr, in dark despair, repeated the words he’d loaded into a suicide prevention app on his smartphone weeks before, fearing moments like this would come.

This was one of his survival plans in a growing national crusade called Zero Suicide.

The movement is marshaling new strategies against rising suicide rates, using smartphone apps MY3 and myStrength to help people build proactive survival plans.

It is intensifying training of professionals who work with people in despair, and compelling more action to take away the means people use for suicide.

These are desperate times for efforts to stop self-inflicted deaths. Many strategies have been deployed to stir awareness and shed the stigma that chokes depression and mental health .

“Nothing has worked,” said Bill Geiss, a Zero Suicide specialist and clinical assistant professor in psychiatry at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. “We are failing miserably.”

The U.S. suicide rate has increased by 7.4 percent. In 2015, 44,193 suicides were completed nationwide.

The notion of achieving “zero suicide” may seem audacious in the wake of these trends, said Scott Perkins, of the Missouri chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

“We’re changing the culture,” he said. “You wouldn’t want an airline to say they hope to prevent crashes, but they can’t prevent them all. With suicide, the goal should be zero.”

Baehr lives in that changing culture. He believes Zero Suicide support is helping him.

The words on his phone were one of the survival strategies the Lee’s Summit teenager built as part of ReDiscover’s Show Me Zero Youth Suicide program.

With quick taps on a specially designed app, he can instantly call up a link to three people he can reach for help, or tap into hotline resources, or call up pictures and reaffirming thoughts he authored when he felt strong — reasons to stay alive.

Some of the people in the Show Me Zero Youth Suicide program write elaborately, or call up memorable verses in preparing their phone pages, said Kirsti Olson, ReDiscover’s suicide prevention liaison.

But Baehr kept his words concise. It’s what he needed, he said.

On that winter day earlier this year, he first called the words up on his phone at school, then retreated to a friend’s house, then found shelter alone in a back bedroom until sleep overtook him.

“I read them over and over again,” Baehr said. “I stared at it for hours … thinking about what they mean to me — how I didn’t want to hurt them.”

The idea of Zero Suicide feels impossible in an Overland Park, Kansas, community center.

Bonnie and Mickey Swade’s Suicide Awareness Survivor Support group gathered 24 people for a regular Tuesday night meeting in the middle of winter.

They are parents, siblings, wives and husbands who know how they tried to stop suicide.

Bob and RoseAnn Brostoski’s son was a physician. He sought out counseling, they said. He was seeing a psychiatrist. Was on a watch list.

“People who kill themselves truly believe everyone will be better off,” RoseAnn Brostoski said.

What chance does a safety plan have, she wonders. She knows the people who surrounded her son, and all the time they spent, “all the hours,” trying to ease his pain.

The Brostoskis want Zero Suicide to work. They want to see lives saved by the safety plans and by healing images and words.

“But you have to accept — we had to accept — the person we love couldn’t access that script for himself,” RoseAnn Brostoski said. “It overwhelmed the damn script.”

The name Zero Suicide came from work that started a decade ago in the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit under C. Edward Coffey, who’s now president and CEO of the Menninger Clinic in Houston.

The most effective strategy, Coffey said, is taking away the means someone has contemplated to kill him- or herself.

Family members, clinicians and friends can learn how someone has contemplated killing themselves, then sweep away the firearms, take the car keys, or remove the ladder or rope.

“They could buy another rope, of course,” Coffey said, “but research shows they don’t. If you can interrupt the idea, it makes a difference.”