By Robert Lloyd

Los Angeles Times

“Wild Wild Country,” a highly pleasurable new documentary series on Netflix, is a dippy tale of the early 1980s in which East meets West and, out of an attempt to build a paradise, all hell breaks loose.

Directed by brothers Chapman and Maclain Way (“The Battered Bastards of Baseball”), its focus is a dimly remembered (but, in its time, nationally newsworthy) religious group — or sex cult, depending on your point of view — led by Indian mystic Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh and the city they set out to build in a remote patch of Oregon.

It’s a story of enemies and neighbors, of power plays and paranoia that includes, among other things, attempted murder, arson, electioneering, bioterrorism by fast food, nude sunbathing, the separation of church and state, 10,000 cassette tapes and 93 Rolls-Royces, one of which the guru would daily drive past his admirers.

“Why do they do this?” a TV reporter standing among them wonders. “What do they believe in?”

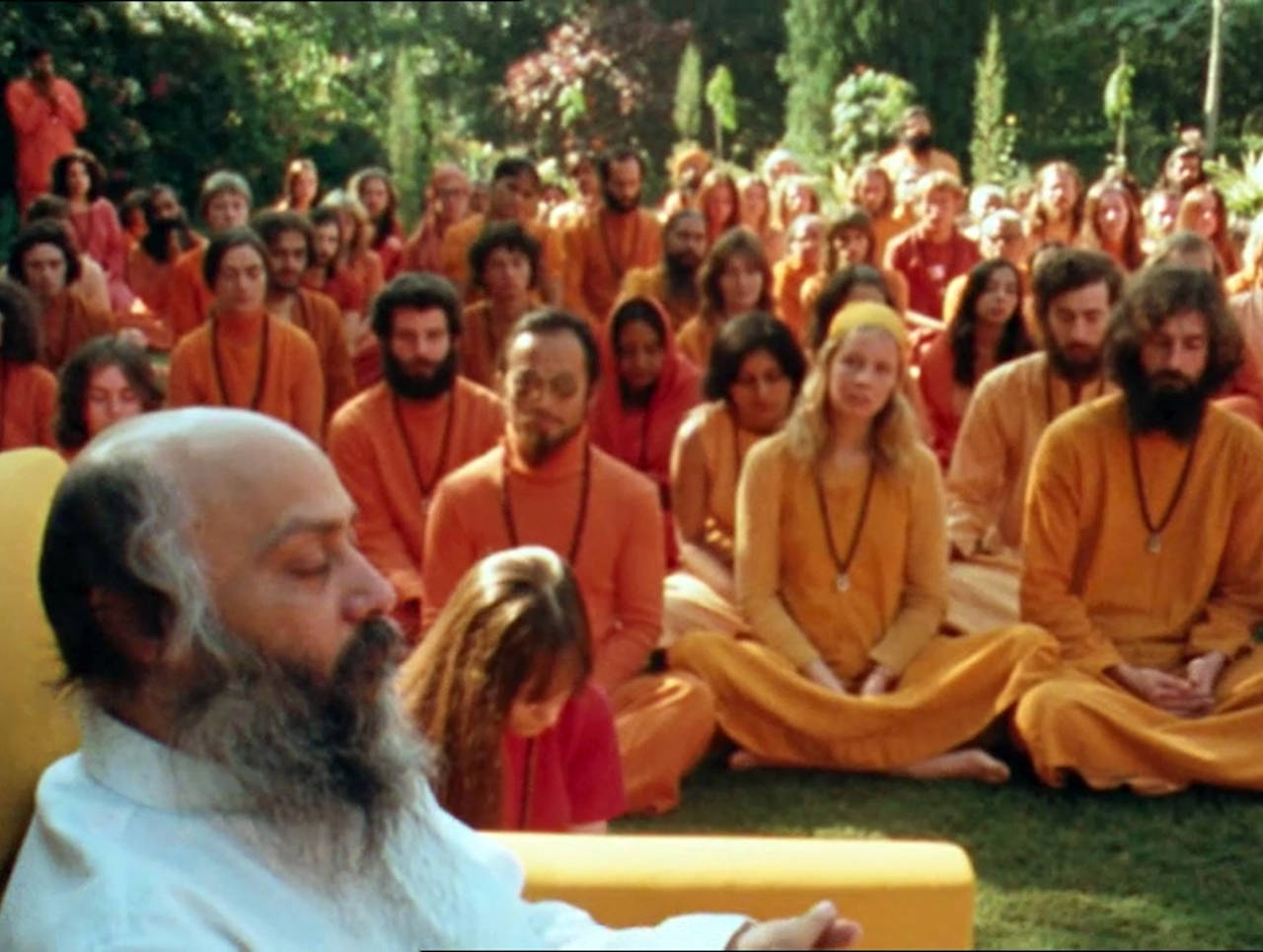

Rajneesh (later called Osho) and his movement caught on in the 1970s, his ashram becoming a destination of choice for mostly Americans and Europeans seeking enlightenment or spiritual thrills. He promoted, among other practices, a brand of “dynamic meditation” that involved hyperventilation (“designed to arouse the serpent force, called kundalini”); primal scream catharsis; jumping up and down and saying “Hoo!”; and, finally, silence and stillness. Then maybe some dancing. This might happen with everybody naked.

At the center of “Wild Wild Country” is Ma Anand Sheela, the Baghwan’s right hand, a powerful and tactically astringent personality who managed Rajneesh’s move to America and the transformation of the 63,000-acre Big Muddy Ranch into Rajneeshpurum, a town with A-frame houses, a shopping center, banks, a pizza parlor, an airport and a population of grinning acolytes in red robes.

In the process, she alienated the people of Antelope, the little “retirement” town at the bottom of the hill and unhappy gateway to the commune that would itself become a pawn in the struggle for local supremacy.

As viewers, we hear little from Rajneesh; rather, we must infer his charismatic power from the faces and the testimony of his followers.

The facts of this case are nothing the world needs urgently to remember; though the shadow of Jonestown was cast across Rashneeshpuram — for those who do not know what Jonestown was, some brief, disturbing clips of that 1978 mass murder-suicide are introduced — this was not Jonestown, bursts of apocalyptic rhetoric notwithstanding. “Wild Wild Country” is not a warning against cults of personality or religious intolerance or fear of the other, although it is certainly instructive on those accounts. The story is almost tragic, but essentially comic, and unexpectedly poignant.

What this is about, at bottom, is the delights of storytelling — the story that the Ways are expertly telling and the sometimes contradictory, sometimes reinforcing stories that their subjects have to tell. The greater point is the wonderful variety of human self-representation, a useful reminder that no two people have the same story to tell, even of events for which they were both present. Every speaker is respectfully presented and allowed to speak his or her piece, and every one is well spoken; rancher or Rajneeshee, government lawyer or commune attorney, each can seem reasonable in turn. The viewer is left to decide who are the more reliable narrators and who the less, and may feel finally that all narrators are more or less reliable — and unreliable.

In the age of the binge, the long-form documentary has become almost commonplace; where one hour seemed sufficient to tell such a story, six do not now seem too much. In the case of “Wild Wild Country,” length gives you time to become accustomed to one reality, one way of seeing things, before it brings in another, and the last crazy plan or misadventure is followed by a crazier one. Still, you feel there may be more to the story — perhaps precisely because there has been so much story already told, and told from so many perspectives.

Well, there is always more to the story; you can say as much of every documentary ever made. But this will more than do.