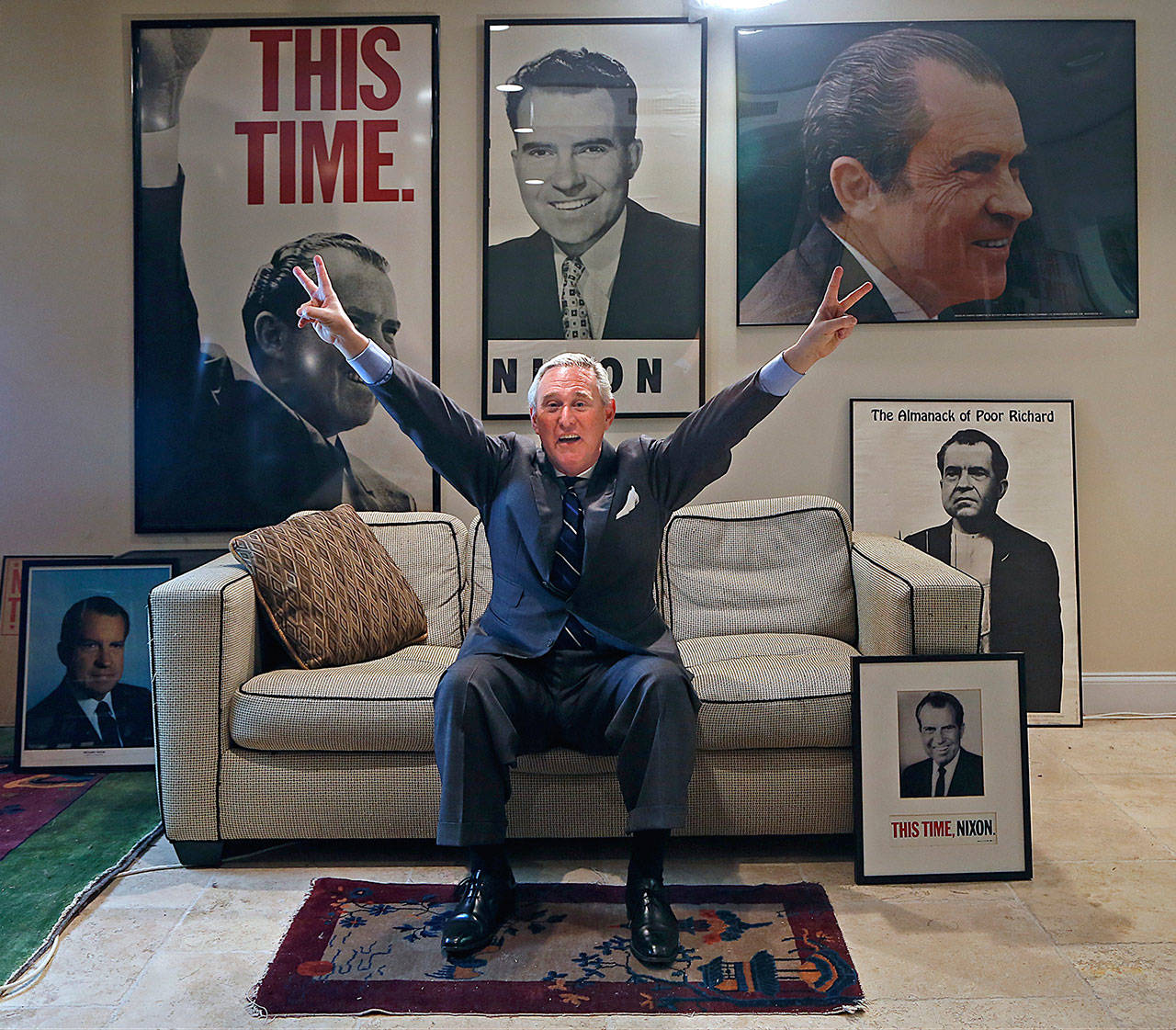

MIAMI — Roger Stone, the legendarily hardball Republican operative who for years has lustily embraced such media epithets as the dapper don of dirty deeds and the undisputed master of the black arts of electioneering, now finds himself on the receiving end of what he calls a political dirty trick — allegations that he helped mastermind Russian leaks of hacked Democratic Party emails — and he’s not liking it much.

“You just wake up one day and a bunch of congressmen are kicking your balls across the field,” Stone said reflectively. “Based on nothing more than a Hillary Clinton campaign meme. … I understand. It’s politics. It’s the democratic process. All I want is the same open forum to respond.”

A steady drumbeat of accusations against Stone that had been building for months — since a Jan. 19 story in The New York Times identified him as one of three associates of President Donald Trump under FBI investigation for links between Trump’s presidential campaign and Russia — reached a crescendo last week, when Stone’s name was mentioned 19 times during a March 20 hearing of the House Intelligence Committee.

None of the references to Stone were flattering. And most ran along the lines of an attack by Rep. Denny Heck, D-Wash., who included Stone among a “rogues gallery” of Trump operatives “who fall somewhere on that spectrum from mere naivete … to unwitting Russian dupes, to willing blindness, to active coordination.”

Since then, the Senate Intelligence Committee has warned Stone not to destroy any written records that could pertain to the investigation. And it’s scarcely been possible to turn on a TV set without hearing calls for Stone to be politically tarred and feathered, or at least subpoenaed.

Political showmanship

The latter would be fine with Stone, who would love a nationally televised forum to counterattack accusations that he labels acts of fact-free political vengeance by enemies he helped whip in the election. The only thing he’s guilty of, he says, is “political showmanship.”

“Don’t confuse me with the character I sometimes play, Roger Stone,” he said. “Millions of people buy my books and watch me on (right-wing radio and streaming-video show) “Info Wars.” They like my style, and yeah, there’s a certain element of over-the-top to my style. But in today’s rapid-cycle media universe, if you don’t have some political flamboyance, you’re nowhere, you’re left behind.”

In an episode fraught with many ironies, among the most profound is that Stone, a longtime associate of Trump who has worked for him mainly on the political aspects of the casino business, wasn’t actually employed by Trump’s presidential campaign last year when the seeds of the Russian hacking controversy were planted.

He had been ousted by the new political team Trump assembled when he formally announced his candidacy. The two, however, remained in touch, much to the displeasure of then-campaign manager Corey Lewandowski. “It was driving Lewandowski crazy,” says one member of the team. “He’d change Trump’s cellphone, and a couple of days later, Stone would get the new number, and they’d do it all again.”

Nor, so far as anybody can tell, was Stone around for the opening shots of the hacking controversy. It started in mid-June last year when the Democratic National Committee disclosed that a private cybersecurity firm had discovered two separate penetrations of its computers by hackers.

The company, CrowdStrike, said the penetrations were done by two separate groups of hackers, one associated with Russian military intelligence and another with the FSB, the current name for the spying agency formerly known as the KGB. The penetrations had begun in 2015 and the hackers had stolen two documents from the DNC computers, CrowdStrike said.

Almost immediately, someone calling himself Guccifer 2.0 (the name clearly an homage to, or an attempt to confuse with, an infamous imprisoned Romanian hacker), began an internet blog in which he took credit for the hacks. He mocked the claim that only two documents had been purloined by attaching a dozen or so more, and added: “The main part of the papers, thousands of files and mails, I gave to WikiLeaks. They will publish them soon.”

Over the next couple of weeks, Guccifer 2.0 posted dozens more documents from the DNC hacks. And, frustrated that he wasn’t getting more attention, he announced he had a Twitter feed and invited reporters to send him questions there, which he would answer in his blog.

Guccifer 2.0

On June 30, he did, offering some general tips about how he got into the DNC’s computers and mocking the claim that he was a Russian. “The guys from CrowdStrike and the DNC would say I’m a Russian bear even if I were a Catholic nun,” he jibed. Guccifer 2.0 said only that he was born in Eastern Europe, which he would later modify to Romanian. (Four months later, U.S. authorities would conclude the hack was done by Russians, though some privy computer security experts say the case is far from proven.)

Guccifer 2.0’s claims, though much-discussed in the world of cybersecurity, got relatively little attention in the mainstream U.S. press. And that was when Stone entered the picture.

On Aug. 5, following a Democratic convention at which Russian hacking was a frequent subject, Stone published a story on the website Breitbart (one of two conservative sites — the other is the Daily Caller — to which he regularly contributes) arguing that the culprit was not the Russians but Guccifer 2.0. Aside from some of Stone’s customary political invective, the story was based entirely on Guccifer 2.0’s publicly accessible tweets and blog posts. There’s no evidence in it that Stone had communicated with Guccifer 2.0 in any way.

But just weeks ago The Smoking Gun website reported that Stone “in the months before Election Day” was “in contact with the Russian hacking group that U.S. intelligence officials have accused of illegally breaching the Democratic National Committee’s computer system.” The contact “came via private messages exchanged on Twitter, according to a source,” said the story. It didn’t report anything at all about what the content of the messages between Stone and Guccifer 2.0 was.

Stone has subsequently released screenshots of what he says are all the messages he exchanged with Guccifer 2.0, about a dozen of them, between Aug. 14 and Sept. 9. Mostly they consist of Stone’s requests for Guccifer 2.0 to tweet out links to Stone’s stories about the election, punctuated with effulgent bursts of mutual flattery. (Stone says he’s “delighted” that Guccifer 2.0’s brief ban from Twitter has ended; “i’m pleased to say u r great man,” replied Guccifer 2.0 in abbreviated tweet-speak.)

Stone dismisses the messages as nothing more than “a classic Washington tummy-rub,” the sort of ad hoc arrangement for mutual self-promotion that is common in the capital’s backslapping culture.

“These messages are innocuous, unimportant, banal,” Stone said. “And they have nothing to do with any conspiracy or collaboration. They occur months after the hacks took place and Guccifer 2.0 began releasing them. The only thing significant about them is that The Smoking Gun had to have gotten them from somebody who hacked, or subpoenaed, my Twitter account.”

Hacked emails

The second prong of the accusations against Stone has to do with a barrage of hacked emails belonging to Hillary Clinton, her campaign chairman and other Democratic Party officials that began to become public the month before the November election.

Some of those emails were, clearly, among the trove of hacked documents delivered to WikiLeaks by Guccifer 2.0. Others came from a different hack, of Clinton campaign manager John Podesta, in March 2016. And some may have come from other sources; WikiLeaks has never clearly identified all its sources.

Journalists have pinpointed at least 12 occasions, starting on Aug. 10, when Stone predicted bombshell disclosures about Clinton or her campaign staff. Almost always they mention WikiLeaks, and several times Stone claimed to be in touch with WikiLeaks boss Julian Assange.

Sometimes Stone was extremely specific (and, it would turn out, extremely wrong) about what was on the way. He said Assange had emails that were deleted from Clinton’s account before the FBI inspected it as part of a 2014 investigation of her use of a private email server for State Department business.

Other Stone predictions were more accurate. On Aug. 21, he tweeted, “Trust me — it will soon be the Podesta’s time in the barrel. #CrookedHillary.” At the time, no one knew that Clinton campaign manager Podesta had been hacked, not even Podesta himself.

On Saturday, Oct. 1, Stone tweeted the WikiLeaks dump was imminent. “Wednesday@HillaryClinton is done. #Wikileaks.” He was off by a few days, but when WikiLeaks began posting Podesta’s emails on Friday, Oct. 7, Stone looked like a prophet to some, a conspirator to others.

Stone now says he was neither, just a guy acting like a journalist, relaying stuff to the public he was hearing from a source close to Assange. That source did not work for WikiLeaks, Stone says; he was an American reporter — “not a Russian, not a spy, not an official, just a left-libertarian reporter,” according to Stone. The source sometimes visited London (where Assange is holed up in the Ecuadorian embassy to avoid extradition to Sweden on sexual assault charges) and was in regular touch with Assange.

The source told him that WikiLeaks was preparing a major document dump. “He told me two very limited things,” Stone recalled. “He said, in a very specific way, that they had ‘everything,’ and that it would be ‘devastating’ to Hillary. From the context in which we were talking, I thought that would include the deleted emails.”

“I had no direct contact with WikiLeaks itself. I didn’t strategize with them, didn’t know their plans, or the scope of those plans, or the origins of those plans, or anything, except that it would ‘devastating.’”

Stone’s prediction that it would soon be “Podesta’s time in the barrel,” he said, stemmed from occasional conversations with reporters who said they were looking into Podesta’s consulting business with Russians. A flurry of stories had already appeared earlier in 2016 based on disclosures in the Panama Papers.

Stone furiously resists the idea that anything he said or wrote about WikiLeaks was an exaggeration. But he does concede that phrases like “backchannel” may have been a little on the James Bondish side for what he now says was actually going on.

“Nothing I said was untrue,” he told the Herald. “It’s showmanship. I wouldn’t describe it the same way at a dinner table, but in a speech setting, you’re gonna use different language. … I thought the tip was good. I was talking to a large audience who I wanted to pay attention and read me and read my books and listen to my radio show and follow me on Twitter.”