Katrina Carrasco’s “The Best Bad Things” vividly creates the world of 1880s Port Townsend; we hear it, we see it, and we smell it.

The warm air of the post office is “reeky with mildew, tallow, unwashed woolens”; an imports office smells of “ink, parchment, the polished sourness of brass”; a decrepit boardinghouse’s hallway reeks of turpentine and sulfur (remedies for a louse outbreak), with a bedroom within smelling of gin and stale vomit. The town itself has a “sweat-and-outhouse” stench; only a prostitute’s cheap perfume —orange blossom, honeysuckle, jasmine — provides a fleeting moment of sweetness.

Into this unwelcoming place of saloons and pleasure-houses and hard-eyed sailors comes Alma Rosales, a former Pinkerton’s detective (from their shuttered Women’s Bureau) now working for Delphine Beaumond, the seductive linchpin of a West Coast smuggling ring — and the object of Alma’s (mostly) unrequited affections. On the trail of opium thieves, Alma’s disguised as her alter ego, dockworker Jack Camp. With breasts bound, hair cropped and hands blackened by a pipe’s grease, she can throw (and, all too often, take) a punch, gain entry to rooms no woman could enter, and seduce smiling good-time girls, even as she pines for her boss.

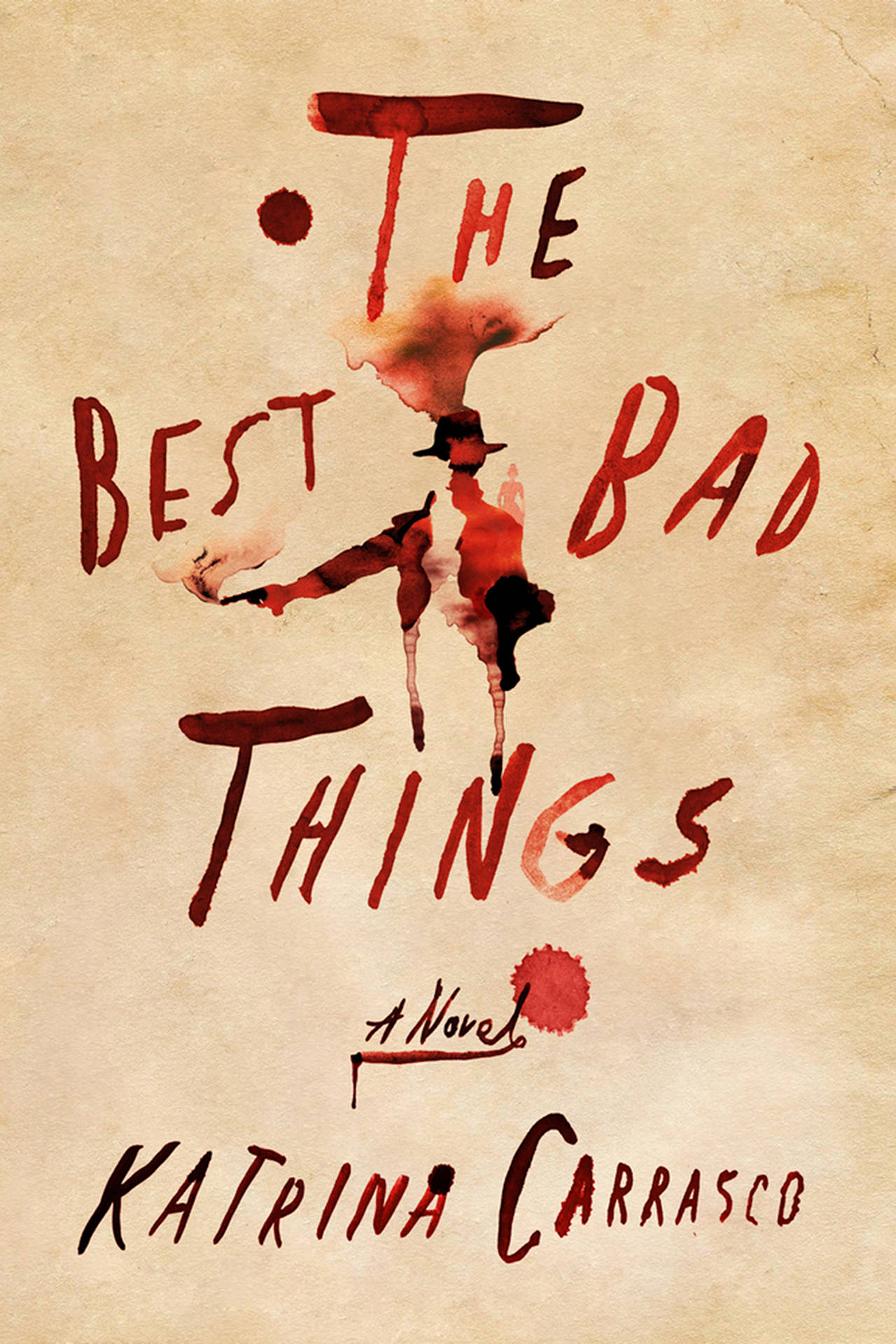

“The Best Bad Things,” whose title is plucked from a phrase in the narrative (“cigars, liquor, diamond studded pistols, pretty company — the best bad things money can buy”), is the first novel from Carrasco, a Seattle resident and M.F.A. graduate of Portland State University. It’s a remarkably ambitious debut, with meticulous research shining from every page. The characters are fictional; the characterization of late-19th-century Port Townsend as a smuggling hot spot is fact, as Carrasco notes in an afterward.

And it crackles like a fast-traveling fire, immersing its reader in a time and place long gone. Impressions and incidents fly at us, sometimes perhaps a hair too quickly (“The Best Bad Things” might benefit from a few more moments in which Alma, and the reader, can breathe) but intoxicatingly so. Carrasco is a gifted wordsmith — “the meaty slap of a punch” rang in my ears, as did countless other phrases — and an imaginative storyteller.

But her greatest creation is Alma, a fearless adventurer who embraces her own duality: female/male, Latina/white (a Mexican American, Alma can change her skin tone depending on how much French-chalk powder she applies), agent/double agent. Despite the ever-present danger of living in a woman’s body, Alma adores performance — and she loves the curious sensation she gets when “toggling between female and male, between Alma and Jack … an undefined space between personas. For a moment, she’s not playing a part or holding a pose, but just being; that sense she sometimes gets in Delphine’s company of truly being seen.”

“The Best Bad Things,” itself irresistibly toggling between crime fiction and literary novel (not that there should be a distinction), is a swaggering introduction to this heroine. Here’s hoping she’ll return soon.